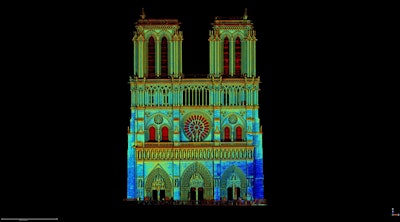

This 3D laser scan of the front of Notre Dame in Paris will help guide architects, conservators and tradesmen in rebuilding the cathedral.

This 3D laser scan of the front of Notre Dame in Paris will help guide architects, conservators and tradesmen in rebuilding the cathedral.When Notre Dame went up in flames April 15, many people lamented the fact that we have few craftsmen today with the skills to recreate the work it took to build the cathedral more than 1,000 years ago.

But while masons, woodcarvers and plasterers may be in short supply, there’s already a small army of high-tech construction specialists seeing to the early stages of the restoration of the world’s most famous church. And the tools they are using—primarily 3D laser scanners and total stations—are the same tools many contractors use today.

In fact, if it weren’t for the scans and digital mapping done on Notre Dame and many of the world’s other ancient monuments, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to repair or restore these world historical treasures. Paper plans for these structures, if there ever were any, are long gone.

Laser scanning started in the late 1980s, and one of the first applications was for historical preservation, says Gregory Lepere, director of marketing for optical and imaging at Trimble. “From the very beginning, cultural heritage was what everybody had in mind,” he says.

Lepere, who is French, grew up fascinated by the Gothic cathedrals in his native country and has performed scans on many of them, including Notre Dame in Paris, as well as assisting in projects in Syria and Egypt. Although he is not currently working on the Notre Dame restoration project, the city has been in touch with him, and he has contributed the data files he’s collected there over the years.

3D laser scanners, like this Trimble TX8 set up in the Notre-Dame de Rodez cathedral, give us clues to past construction, monitor movement and changes, and create a digital record for future architects and historians.

3D laser scanners, like this Trimble TX8 set up in the Notre-Dame de Rodez cathedral, give us clues to past construction, monitor movement and changes, and create a digital record for future architects and historians.(Photo credit: Christophe BOIS – Géomètre Expert

“The scanning is going on as we speak, but the cathedral has been scanned multiple times for different reasons,” says Lepere. “They have a database of information from different points in time that they are going to use. It’s not just a one-time thing. During the next year or two, the cathedral is going to be scanned many times.”

While these digital scans won’t stand up the beams or rebuild the roof, the information they capture is vital in the planning process for rebuilding and to make sure the remaining parts of the structure have not moved or changed in any way that might need corrective action.

“I assume that the stones are still good,” says Lepere. “That will be determined with laser scanning. The fire or heat could have destabilized the walls or changed them. One thing we know is that the north wall was supported by a wooden structure that has been destroyed. The question to be answered is whether the wall has moved or is it still good? This is critical.”

Seeing what the eye can not

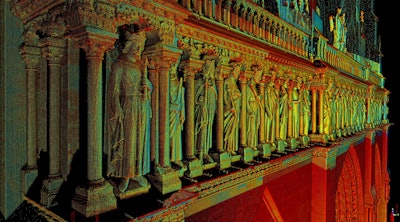

Exceptionally accurate 3D images, like these statues in the front façade of Notre Dame, can be captured to help future craftsmen recreate the artwork should it ever become damaged or destroyed.

Exceptionally accurate 3D images, like these statues in the front façade of Notre Dame, can be captured to help future craftsmen recreate the artwork should it ever become damaged or destroyed.Laser and total station scans do more than provide a digital blueprint of a structure, Lepere says. When the data are analyzed carefully, architects and archaeologists can sometimes discover anomalies that aren’t apparent to the naked eye.

In one example Lepere cites, the scan of a cathedral in his hometown of Amiens, France, where the scans showed a slight asymmetry between the right and left side of the structure, and one of the balconies was out of level by just a few centimeters. Using this information, historians determined that construction had stopped and then restarted many years later. “We helped them understand how it was built and how it is moving,” he says. “Buildings are not static.”

Knowing this, architects, archeologists and others now routinely scan and monitor these historically significant sites with lasers and total stations. “It’s not just about acquiring the shape of the monument, but we also have technologies to permanently monitor them, putting small prisms or stickers at certain points and then have the total stations monitoring 24/7 to make sure nothing is moving.”

Although his role at Trimble today is primarily marketing, in his 20-year career with the company, Lepere helped design and engineer many of these tools.

In these applications, the laser scanners are used for rough accuracy. When it comes to details like statues, wood carvings and plaster moldings, the laser can be tuned for a slower, more accurate scan, down to one millimeter, or a total station can be used. But none of these tools would be unfamiliar to today’s contractors. The same tools are used to scan highways, bridges and buildings.

“These are completely off-the-shelf solutions,” Lepere says. “The professors, universities and surveyors who do this are our customers.”

Pieces of the puzzle

The orange triangles are laser scanner positions. Scanning from multiple locations helps to develop a complete 3D image of all facets of the structure.

The orange triangles are laser scanner positions. Scanning from multiple locations helps to develop a complete 3D image of all facets of the structure.“One of the first projects I worked on was to give our scanners to archaeologists who had been scanning the tombs and temples in Egypt,” says Lepere. “The need was to capture the reality, specifically with large monuments where we don’t have blueprints and we don’t know how they were built.”

The trouble was the structures had been wrecked many centuries earlier. “It was a field of stones,” says Lepere. “It looked nothing like a building.”

But by carefully scanning each stone and analyzing their shapes and markings, the archaeologists were able to virtually rebuild the original temple by treating each stone as a piece of a giant 3D jigsaw puzzle. “We were able to create something no one had seen in a very long time,” Lepere says. “That was an extraordinary moment.”

“This is why I’m so passionate about this technology,” he says. “Things like this and Notre Dame are pushing us at Trimble to think more about creating new tools that are easier, faster and more accurate to capture all these marvels of the world.”

This Syrian monastery where Saint Simeon is said to have preached for four decades in the 5th Century was damaged by a Russian rocket attack in 2016. Fortunately, this digital scan of the site, taken in 2006, remains.

This Syrian monastery where Saint Simeon is said to have preached for four decades in the 5th Century was damaged by a Russian rocket attack in 2016. Fortunately, this digital scan of the site, taken in 2006, remains.