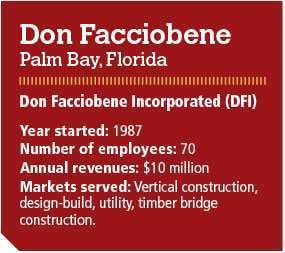

After starting his construction company in 1987 in his hometown of Palm Bay, Florida, work began drying up in 1990. By 1993, Facciobene’s company had been decimated – only he, a secretary and one other employee reamined. He had just finsihed the building that houses his office and, at the time, an auto parts store that provided quite a bit of income through rent. When the auto parts store went under, Facciobene was forced to think outside the box for income.

So when he got the opportunity to replace light bulbs at the top of water towers in and around Palm Bay for $275 a pop, he took it without hesitation. He took it even though he had never climbed a ladder that high before. He simply asked an electrician friend for a few tips and started climbing the first tower. “I was scared to death,” Facciobene recalls. “Shaking, scared to death the whole way. But I was in a bind.”

If only climbing had been the only obstacle. As he reached the top of the tower, he was greeted by a giant nest of hornets. Most would have called it a day at that point and made their way back down. Maybe some would have given it another shot equipped with a can of bug spray or a beekeeper’s mask. Facciobene on the other hand, not interested in making this trip any more times than was necessary, simply climbed through it, changed the bulb and climbed down.

Though he signed on to do 10, Facciobene only did one more tower himself before finding someone else who would do the remaining jobs for much less than the $275 he was being paid for each one. “So, I ended up subcontracting the rest out and making money on it,” he says with a smile.

Since then, Don Facciobene Incorporated (DFI) has seen more ups and downs. But through it all, Facciobene has always come back strong, largely due to a relentless dedication to his work and a willingness to diversify his business in surprising ways.

So, yeah. You could say that the water tower was the low point of Facciobene’s career. But really, it was the ladder to higher ground.

Getting skinny when you need to

Facciobene is a second-generation builder. His father moved the family to Palm Bay in 1962 when Facciobene was 3 years old. His father was interior contractor and when the kids were old enough, Facciobene, his brother and his sister started working for the family business. In the late 1960s, his father opened up a paint and decorating store and supplemented the business by buying and remodeling homes and building new ones.

Facciobene says he learned valuable lessons working in that paint store. “We never missed work, we never missed school, we never missed dinner and we never missed church,” he says about his childhood. “My father always joked that we had plenty of time to do other things as long as it was on Sunday afternoon, after church.”

When he started DFI in 1987, the company was a general contractor doing primarily concrete and masonry work. Being such, the first machines the company were a Massey Ferguson 139 with a box blade, a Class 6 dump truck and various concrete equipment. “Then I quickly realized I had nothing to load the dump truck with so I bought a Bobcat,” Facciobene says.

“The biggest lesson I learned was don’t get a machine that you think will be too small,” he says. “My weapon of choice for an all-around machine was a rubber tire backhoe. Skid steers have been popular for me on the vertical side. And I don’t know how I ever survived without a full sized dump truck.”

He spent the first 8 or 10 years without a mechanic, choosing instead to keep all the machines running himself with the help of his employees. “That was a huge challenge keeping all of that running. I was always a gear head, but when I had grown to four or five pickups that’s when I decided to hire a mechanic.”

Though the company experienced a rough stretch in the early 90s, things got going again in 1994 when DFI began doing work for an architectual firm. In 1996, the company won the bid to build a 40,000-square-foot church and things caught fire after that. In 1999, the company built four hotels and around that time branched out into building timber bridges.

Ten years in, DFI dropped masonry, at one time its core business. The company now does primarily private work, concentrating on vertical construction, design-build, utility and the timber bridge construction markets. It’s even doing a bit of industrial maintenance. Facciobene timber bridge work has been a key generator of revenue for the company. DFI builds these timber bridges all across the country, primarily at parks, but also at golf courses, retail stores like Bass Pro Shops and even at nearby Walt Disney World.

By 2006, the company was bringing in $20 million in revenue per year. Despite the success, it wouldn’t be able to escape the long reach of the economic downturn. In 2011, annual revenue had dropped to $5 million.

Facciobene credits his focus on keeping a small debt-to-equity ratio and the timber bridge business for help in working out of the downturn and back to $10 million per year. “As has been evidenced in the last six years, you never know what tomorrow will bring,” he says. “We’ve always had the ability to get skinny when we need to.”

Keys to success

In addition to his conservative financial sense, Facciobene points to his company’s customer service as the key to its success.

“I had the fortune to have to work in retail a little bit. In retail, it’s always about pleasing the customer. I was shocked by how most people in the construction business don’t know anything about how to make their customers happy,” he says. “Many don’t understand how not showing up with the proper crew or not following through with what was requested frustrates people. Those industrial maintenance contracts? They keep us around because we know how to act around high level people and in highly-occupied places.”

When asked what the most challenging aspect of starting his company was, Facciobene says for him, it was learning how to manage employees. Difficulty aside, he says his employees have always been a main focus for him and he’s always worked to keep them safe, busy, happy and motivated.

“I think I’m able to do it by my one-on-one relationship with them. I know their families and friends. I know what makes them tick. I know where they live, what they do,” he explains. “I work with them. When they have issues I help resolve them. I go out of my way to do whatever I can do for them to make them happy and make them comfortable.”

A more recent challenge for Facciobene and contractors across the country has been finding qualified craft workers. “The average age of our tradesmen is getting older and older,” Facciobene says. “I do have some young guys that I’ve been in able to plug in and grow and I’m encouraged by that.”

While many firms formed partnerships with apprenticeship programs and others have started their own training programs, Facciobene says he has begun scouting for younger workers he feels he could train up on the job. “I’m constantly recrutiing younger kids,” he says. “I scout particular types that are independent, disciplined and have good morals.”