Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series. To read part two, click here.

Part 1: The scope of the problem

Toxicology reports showed evidence of marijuana and codeine in Benschop’s blood. He already had a long rap sheet, including 11 arrests on charges including drugs, theft and weapons possession. Benschop was arrested and eventually sentenced to 7 to 15 years in prison for manslaughter. The construction contractor, Griffin Campbell, directing Benschop’s work, was sentenced to 15 to 30 years. The building inspector for that area, Ronald Wagenhoffer, committed suicide a week after the incident.

This tragedy, and the drug use that contributed to it, is no isolated incident. The construction industry has a drug problem – a huge one.

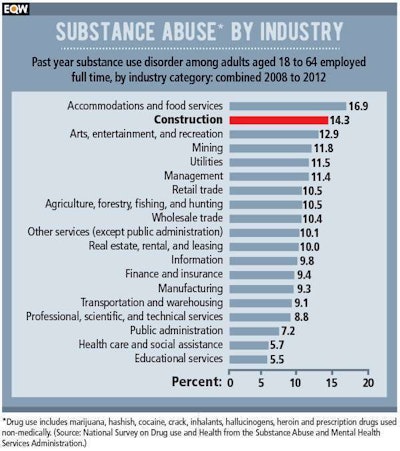

Second sickest industry

Some 12 percent of construction workers use illegal drugs monthly, double the national average. That’s more than one out of every eight of the workers around you – the guy driving the truck past your crane, the guy on the excavator, the flagger on your busy roadside construction site.

Complicating the issue are the country’s contradictory laws concerning marijuana use, which pose difficult personnel and legal issues for employers. And the widely-reported opioid abuse epidemic is in part due to medications prescribed for pain from job-related injuries that are all too common in construction.

A history of problems

The passage of the Drug-Free Workplace Act 25 years ago helped lower drug abuse rates in all industries. But the numbers are still cause for alarm given the dangerous nature and the high rate of accidents and fatalities in construction work.

In the construction industry, it is not uncommon to find 25 to 35 percent of pre-employment drug tests coming up positive, according to the insurance and risk management firm IMRI. Even when construction workers know they are going to be tested, 3 to 5 percent still test positive.

And drugs bring big problems. The Department of Labor says drug and alcohol abuse contribute to up to 65 percent of on-the-job accidents and up to 50 percent of workers’ compensation claims. Substance abusers are absent from work an average of five days a month, are ten times more likely to steal from the company or other employees, use three times the normal level of employee health benefits and incur 300 percent higher medical costs.

Drugged out nation

Last year the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that “almost half of all Americans take prescription painkillers, tranquilizers, stimulants or sedatives.” Codeine, such as was found in Sean Behschop’s drug test, is one such drug.

Some 119-million people, 45 percent of the population over the age of 12, took prescription psychotherapeutic drugs. Of those, 19 percent didn’t have a prescription and 5 percent of those say they got the drugs from a dealer. All told, 16 percent of all prescription drug use is actually misuse.

This widespread illegal substance use is a contributing factor to the construction industry’s high injury rate. The evidence comes from construction companies that have implemented drug testing.

According to a 2001 Cornell University study, construction companies that instituted drug testing policies saw a 51 percent reduction in injuries within a two-year time span. Additionally, companies with a drug testing program show an 11 percent reduction in workers’ compensation claims.

Marijuana, the often legal high

The election of November 2016 brought legalized, recreational marijuana to four new states: California, Maine, Massachusetts and Nevada. When you add those to the states and districts that allowed recreational marijuana before the election – Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Alaska and the District of Columbia – there are now 75 million people living with access to legal pot. That’s more than one-fifth of the population of the United States. (See chart “Where marijuana is now legal” below.)

Just one year into Colorado’s experiment with full legalization for recreational marijuana, some disturbing statistics began to emerge.

And while it may be legal, contractors around the state are united in their refusal to hire – and willingness to fire – anyone who tests positive for the drug. It doesn’t matter if workers toke up only on weekends. Zero tolerance means zero tolerance.

“We are upfront that we will not accept an applicant if they are consuming drugs or alcohol,” says Dan Starr, president of the construction company GE Johnson. “That tends to weed out about 90 percent of them.”

Starr says the zero tolerance attitude prevails across most companies in the state and that being up front about it has actually helped reduce the number of job applicants who fail the drug test. “The rejection rate is much higher for those companies that don’t make that clear,” he says.

In addition to its pre-employment drug screening, GE Johnson also does random drug testing throughout the year. If an employee fails, they are fired immediately, but after 90 days they can reapply and come back to work if they pass the test.

The problem is relatively rare. In the past five years the company has only had to fire one long-term employee who failed a drug test, says Starr. In an ingenious way, part of that success may be due to GE Johnson’s “stretch and flex” program, where the crews do a few minutes of warm up exercises every morning before work.

The warm up is ostensibly to prevent muscular-skeletal injuries, but it also allows foremen to gauge the fitness of employees before they start work. If somebody is having trouble balancing, they may be sent home. If they show up ripped and red-eyed, their supervisor knows it immediately.

And while the rest of Colorado may be celebrating the legalization of marijuana, Starr is firmly against it, to the point where his company will not build or work on any of the greenhouses and buildings being put up to grow and process the plant. In an interview with the Colorado Springs Gazette, he was blunt: “This is a very troublesome issue for our industry, but I do not see us bending or lowering our hiring standards,” Starr said. “Our workplaces are too dangerous and too dynamic to tolerate drug use. And marijuana? In many ways, this is worse than alcohol. I’m still in shock at how we (Colorado) voted. Everyone was asleep at the wheel.”

The Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, a federal research organization, found that the number of fatal crashes in Colorado in which one driver tested positive for marijuana rose from 8.1 percent in 2013 (the year the drug was legalized in the state) to 12.4 percent. They also found that marijuana was involved in 20 percent of traffic fatalities compared to just 10 percent five years ago.

The AAA Foundation for Safety found similar results in Washington state where the percentage of drivers involved in fatal car crashes who had recently smoked marijuana increased from 8 to 17 percent in 2014.

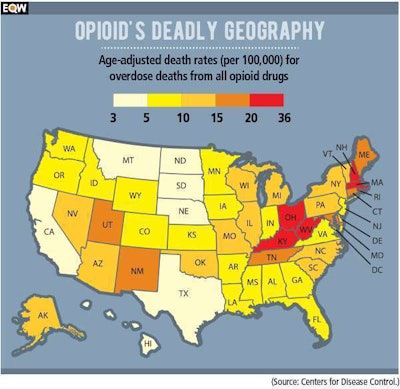

Opioids’ deadly track record

Construction workers spend more on opioid prescriptions than any other occupational category, says Liz Griggs, chairman and CEO of Canterbury Health Care. Griggs also cites a survey from the insurance firm CNA Financial that reports the construction industry has the highest rate of opioid addiction in the country, five to 10 percent higher than the general population.

The news is filled with stories about the nation’s new opioid epidemic. Part of the problem results from over-prescription of painkillers, but a more sinister development is the rise of cheap heroin.

In his book Dreamland, Sam Quinones says the new dealers are low-profile young Mexicans who deliver nearly pure black tar heroin to whoever needs it, whenever they need it. Heroin has moved out of the ghetto and into middle class and working class life with a nearly foolproof marketing and distribution plan. Dealers choose rural markets and places where they don’t have to battle with existing gangs, avoiding New York and Chicago and concentrating on places like Portsmouth, Ohio, and Boise, Idaho. (See chart “Opioid’s deadly geography” below.)

Quinones also says that some 70 percent of these heroin addicts started out with prescription pain medications – the same kind of painkillers often prescribed to construction workers who are injured on the job.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the combination of over-prescription of pain meds, dirty doctors and their pill mills and easy-to-obtain black tar Mexican heroin has resulted in some 100 overdose deaths a day in the United States. In 2016, heroin deaths surpassed gun homicides. And opioid-related deaths of all kinds have surpassed the number of vehicle deaths in the United States as well.

Methamphetamine: productivity’s best friend

Among many blue collar workers, using methamphetamine is the way to get things done.

The initial rush from ingesting meth brings increased energy and alertness, an elevated positive mood state and decreased appetite. Compared with other stimulants (e.g., cocaine) the high lasts much longer, ranging from eight to 12 hours. Users can get high in the morning, work like a fiend all day, come home, play with the kids, tune up the car and paint the house before the drug wears off.

But what goes up, must come down. And with meth, the landing is brutal. Methamphetamine use has been linked to many psychiatric difficulties, such as depression, irritability, insomnia, paranoia and aggressive behaviors.

SAMHSA says that workers in the restaurant, construction, factory, and mining industries, along with white-collar workers and truck drivers fall prey to the allure of boundless energy and alertness that meth brings. According to a joint study compiled by Rural Center for AIDS/STD Prevention, a study of meth users in rural Colorado found that use is particularly prevalent among workers in construction, agriculture, oil production and other occupations that demand long hours and/or tedious tasks.

Anthropologist Jason Pine embedded himself with a group of meth users in Jefferson County, Missouri, over the course of nearly a decade. In a 2013 interview in the New Republic, Pine said: “Many of the people I met began meth on the job – concrete work, roofing, trucking, factory work. It’s a way to make the job easier, to work longer hours and make more money.”

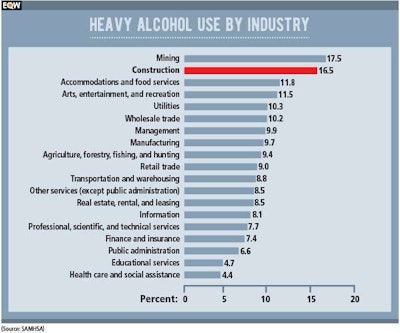

Alcohol

While the main focus of this series is illegal drug use (and marijuana even where it is legal), alcohol abuse creates many of the same problems.

In February last year, New York City-based WABC television uncovered a group of construction workers from four different Manhattan jobsites engaged in heavy lunchtime drinking (four and sometimes five drinks each) on three different occasions – including workers who were tasked with rigging crane loads and operating equipment.

Reaction was swift. The contractor, Gilbane, fired several of the workers. And some in the city government have called for mandatory alcohol testing.

The incident points to a much larger problem, uncovered in SAMHSA’s survey of heavy alcohol use by industry: mining and construction take the number one and two spots respectively.