The No. 1 killer of workers in road construction is struck-by accidents, according to federal statistics and industry experts.

Those risks are coming at workers from both sides of the orange cones and barrels they work behind – from motorists crashing into the zone and from coworkers not following proper safety procedures.

“We call the cones and the barrels the orange line,” says Lee Cole, vice president of environmental, health and safety at CRH Americas Materials. “So on one side of the orange line is the protection of the motoring public. The other side of the orange line is protection of the worker. …

“And it’s a thin orange line.”

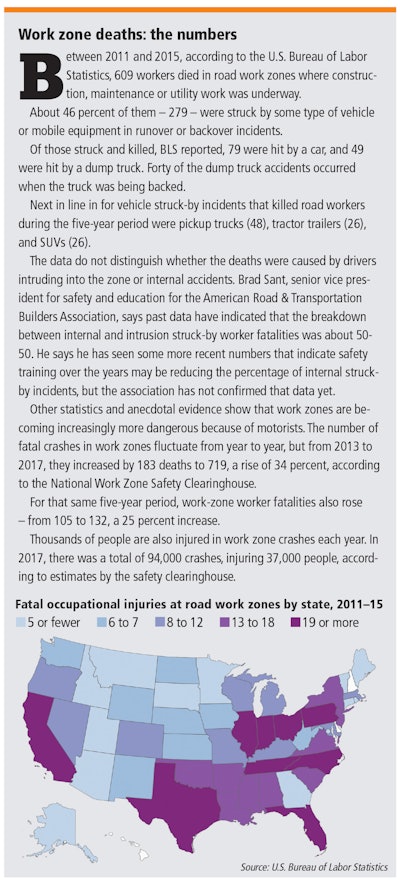

The rising death toll and high number of injuries (see sidebar below) have led the roadbuilding industry to launch public service campaigns to make drivers more aware of the dangers of work zones. At the same time, it is developing innovative ways to protect workers while also stressing the importance of safety training for all involved in roadwork, from planning to construction.

Work zone intrusion

“Most people nowadays, when they get in the car, feel weird if they don’t have their seat belt on, and know it’s really stupid to drive if they’ve had a couple of drinks,” says Brian Turmail, spokesman for the Associated General Contractors. “But few people seem to have the impression that it’s really stupid to go speeding through a work zone.”

Each year, AGC members respond to a Highway Work Zone Safety Survey. In 2016, 39 percent of surveyed construction firms reported an intrusion crash in a work zone. This year, the number rose to 67 percent.

In response, AGC launched a public service campaign. The message: driving safely in work zones doesn’t only protect workers but protects drivers and their passengers as well.

For instance, 132 workers died in road work zones in 2017. But in all, there were 710 work-zone crash fatalities reported that year, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

This campaign asks motorists “to act in their own self-interest,” Turmail says, “because they’re the one who’s most likely to get injured or killed in a highway work zone.”

Following best practices within the zone

Along with public service campaigns, the industry continues to focus on improving training and pushing best practices for road workers.

For the past 15 years, the American Road & Transportation Builders Association has offered its internal traffic control planning program, training about 40,000 industry members as well as state transportation agencies, says Brad Sant, senior vice president for safety and education. One of the big pushes of the program is to think of work zone safety as an overall process rather than a piecemeal approach.

For example, one technique is to create separate equipment-free and worker-free areas. “Create acceleration and deceleration zones, not just for the traffic side but also on the internal side and make sure those are clear and that no workers are assigned to work there,” he says.

That also means ensuring the portable toilets, water coolers and employee parking areas are not located where workers have to cross lanes used by work vehicles and equipment.

“Sometimes you talk about this and people think, ‘Oh, you’re just making us do more work,’” says Sant. “But when you plan the process and the workflow and the traffic pool and where the workers are, you’ve not only created a safer work zone, you’ve actually created one that runs much more efficiently. So it’s actually a business incentive.”

On the road

“One of our biggest initiatives and responsibilities we have before sending an employee to the field is to make sure they are properly trained,” says Dwayne Edmondson, Gallagher Asphalt’s safety director. The company has won numerous industry awards for its excellence and safety, including Diamond awards from the National Asphalt Paving Association.

“I preach ‘be in command and demand respect’ when you’re flagging and make sure you’re communicating with your crew and with the motorist,” Edmondson says.

Just recently Edmondson was out in the field in the Chicago area and saw that worker-to-worker communication pay off. A car driver wasn’t paying attention, failed to stop for the flagger’s stop sign and came speeding into the work zone. A worker was about to cross the street when another worker beeped his horn and yelled to him. The worker stopped abruptly. “We deal with a lot of this stuff on a daily basis,” Edmondson says.

And if the driver starts to get out of hand, “we encourage our employees to maintain their position but contact their foreman immediately through the radio.”

He also encourages flaggers to communicate with motorists to help prevent potentially volatile situations.

“People respect you when you’re in control,” he says. “This is what I tell my guys all the time: ‘Get eye contact with the drivers. Motorists need to hear your directions. Most of the time the driver doesn’t have a clue of what’s going on; they’re looking for a sense of direction. It is our responsibility to help in that effort.’

“If we can’t provide that, they typically get agitated and develop a lack of respect for the flagger,” he adds. “So I tell these guys, ‘Communicate with the motorist; let them know we’re paving, and we should be letting you go soon.’”

To prevent backover incidents, Gallagher always deploys a well-trained designated “dump man” to its work zones. Everyone knows the dump man, Edmondson says. He wears an orange safety vest, while everyone else wears lime green, so he stands out.

He’s the only one who acts as a spotter for the dump trucks, and the truck drivers know they’re not supposed to move unless they are given directions from the dump man to do so.

When a truck hauling asphalt approaches the site, the dump man halts it until the paver is ready for loading. He also handles the load and unload tickets. The dump man communicates with the driver and then ensures no one is nearby or in any of the truck’s many blind spots.

“He literally controls that whole situation,” Edmondson says. “The dump man has a huge responsibility.”

Edmondson believes in instilling a heightened sense of awareness among the workers, starting with their first day on the job. After new employees go through safety training that involves real-life scenarios to simulate what’s happening in the field, he also goes out on the job with them for follow-up to make sure everyone understands what they’re doing and to answer any questions.

“You’ve got to let these employees know from the get-go how serious it is,” he says. “If you don’t, they’re going to take it for granted, and they could potentially lose their lives.”

Becoming AWARE

But sometimes, training and best practices aren’t enough to keep road workers safe.

In 2013, CRH Americas Materials (then known as Oldcastle) lost four workers in a series of devastating crashes in separate work zones. A drunken driver crashed into two workers on the back of a paver; 18 hours later, a flagger was killed in another part of the country by a distracted driver on a cellphone, and in another fatality, a drunken driver crashed into a compactor, pinning a worker.

“A distracted driver, whether by intoxication or cellphone, is an incoming threat like that missile,” Cole says. “Maybe this system can be adapted and alert workers.”

Five years later, CRH has deployed and is seeing positive results from the new technology it calls AWARE, which stands for Advanced Warning and Risk Evasion. AWARE consists of two systems: Lane Intrusion and Sentry.

More than 100 Sentry units are already being used on CRH work crews. It is designed for workers on two-lane road projects with flagging operations. Using radar and GPS, the system detects when a vehicle is approaching a work zone at high speed or if a driver waiting at a flagger’s stop sign tries to pull out and go around. The system alerts the driver by flashing light and sound, and it sends a warning sound and vibration to a pager-sized device worn by the flagger. It also sends warnings downstream to other workers.

Cole points to a recent incident in Alabama in which a distracted driver blew past a flagger. “The flagger had already gotten the alert long before the driver got to him, and he was out of harm’s way, off the road away from it,” Cole says. The distracted driver eventually stopped, causing no injuries.

The system also has a video component, allowing CRH to review incidents. Cole says the company has plenty of videos of cars driving past flaggers, getting the warning and then getting back into position.

“We’re really seeing now the benefits of the past five years – lives being saved, workers excited about going out there,” Cole says. “If you almost get hit by a car one day, you really don’t want to go back out there the next day. With this system, our folks really feel like they’re protected.”

The second AWARE component is the lane-intrusion system designed for working on multilane highways with speed limits of 50 mph and above and when a lane is closed with advanced warning signs. A radar perimeter is established so that any intrusion beyond the cones or barrels alerts the distracted driver with audio and visual warnings. Workers are also alerted, and the pavers and compactors have AWARE alarm units on them as well.

This lane-intrusion system is still being developed, but Cole expects it to be ready for use next spring. He also notes that it is not the sole answer to preventing accidents. “We realize that we should not depend solely on technology to protect our workers,” he says, “but rather use the best practices that we continue to develop in conjunction with technology to provide the best defense.”

Positive protection

Some in the paving and construction industry would like to see more use of barriers between traffic and workers, known as positive protection, and for the federal government to provide funding or incentives for their use.

Sant says there are several types of positive-protection devices that have been developed in the last 15 years that can help protect workers from intrusion. Those include mobile barriers that can be set up for short-term repairs on an interstate. The systems are rigid-wall, semi-trailers connected to tractor trailers.

Steel barriers instead of concrete barriers are another option. Though steel barriers are more expensive, they are lighter and easier to transport, which can lead to lower transportation costs, and they can be installed quicker, Sant says.

State DOTs have also seen success over many years with crash cushions mounted on the back of unoccupied vehicles to protect workers from errant drivers.

The device came in handy in a recent incident in California, when a driver became distracted while reaching for a cup of coffee and headed toward a Caltrans mowing crew. The car hit the cushion instead of a worker, who saw the vehicle coming, ran up a hill and took shelter behind a tree, according to Heidi Crawford Ruiz, Caltrans public information officer.

DOT deploys auto-flagger

Two flagger deaths in the past two years led the Oregon Department of Transportation to expand its use of automated flaggers. The devices can be controlled remotely by a flagger standing out of harm’s way.

A human flagger can operate two of the devices if both of them are in view, and on larger projects, a worker is assigned to one auto-flagger each. ODOT only uses them on brief projects on two-lane roads with work zones less than 800 feet long, says Katherine Benenati, assistant communications manager.

“The Automated Flagger Assistance Devices will not only keep our human flaggers safer on the job, they also warn workers that a motorist has passed the auto flagger, and that warning may be the difference between someone going home tonight or not,” she says.

The auto-flaggers are primarily being used in eastern and central Oregon, with plans to expand them statewide.

Seeing it every day

Many of the stationary devices, such as barriers and auto flaggers, are typically used for nonmoving paving and road operations. And barriers are not always allowed by state departments of transportation on moving asphalt projects due to traffic and other concerns.

“In the asphalt paving world, the entire work zone is mobile, it’s constantly moving,” Cole says.

“We have to depend on other things.”

And with increasingly distracted drivers, it becomes even more crucial for workers to be visible to the public night and day and for contractors to have well-planned internal and external traffic control on either side of that orange line.

“We have to go beyond compliance; we have to go beyond the rules and regulations,” Cole says.

And above all, workers must be trained to stay alert.

“One of the most dangerous things that can happen to a worker that can put him at risk is becoming complacent,” Cole says.

“Complacency is probably our worst enemy.”