That means it’s time for a serious talk and, fortunately,

The threat of “the red chairs” is far from the only safety measures in place at the company, but their status attests to the profound respect Thomas’ employees have for their boss, who is equal parts mentor and father figure.

Some might think teacher and contractor are on opposite ends of the career spectrum. But Thomas, whose first career was teaching, blends the two careers naturally with a warm personality. It’s his direct involvement and concern for his employees that has built his company into a success.

Tim Zinkham, supervisor of engineering services with Cranberry Township near Pittsburgh, says the company is the first he calls when they “get into a pinch. We continue to call them back because of their morals and the ethics they have,” he says. “We have worked with several different crews and foremen. If Thomas is on the job, we don’t have to worry about performance.”

And it’s the company’s attention to detail and Thomas’ respect for the process of ensuring safety requirements are met that made the company the clear pick for the Safety Award in our 2014 Contractor of the Year contest.

The growth of a diverse company

Thomas graduated from California University of Pennsylvania in 1974 and took a job teaching industrial arts in Grove City. But when a teachers’ strike forced him to seek a more stable living, he decided to give construction a try.

“I was going to make a blistering $8,000 a year for that first year of teaching. I didn’t have enough money to withstand a strike so I decided to do a little bit of remodeling,” Thomas recalls.

Within six years, he had started his own business.

He incorporated the business in 1985 and embarked on his first major project, a housing development. Thomas says. “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I didn’t understand all the parameters and the cost so I went into it with a little bit of naiveté.”

Thomas did a majority of the work himself, from designing and pricing the jobs to driving nails on site. It proved to be a trial by fire, but he persevered and eventually ended up adding an excavation business, Rock Excavation, to his company.

He also gained a mentor. “Joe Gaunts was the township engineer and he practically did it on a volunteer basis. He took both the township’s perspective and my perspective. It was the kind of relationship that is rare. He wanted to make sure the township got what it needed and that I got what I needed,” Thomas says.

Since then, Thomas has also added Pine Grove Environmental, which mediates contaminated industrial sites. He says the company is also in the process of getting the permits together for entering the aggregate business.

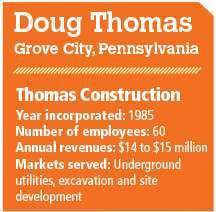

Today, Thomas Construction does an even amount of work for public and private customers and brings in between $14 million and $15 million each year, serving the underground utilities, excavation and site development markets.

“In this region, in order for us to grow to the size we are, we needed to be diverse,” Thomas says.

The burden of regulations

When discussing the challenges of running a construction business with Thomas, the usual talk of struggles with leadership and managing a company don’t often come up. Instead,

“I don’t think I could start this business today,” Thomas says. “It would be too difficult to start it today with all those regulations.”

As an example, he cites the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit program, which controls water pollution by regulating potential point sources. “In the past, the NPDES permit was only necessary if you were going to disturb 50 acres. Then it went to 25, then to 12, then to 5 and now it’s down to one. We have engineers now that all they do is chase permits,” Thomas says.

“We understand the need of those types of regulations and we don’t want to do anything that’s harmful to the environment. I just feel like more timely responses from the government agencies would be incredibly helpful.”

Serious safety

Thomas takes safety seriously. “I don’t want to see our people hurt,” he says.

The company has a safety committee and a mod rate of 0.60. Thomas says he is not part of the safety committee because he wants the process to remain objective. “They’ve done a marvelous job,” he says. The company’s business manager, Tom Friedel, also acts as head safety officer.

Thomas says the company has a tool box talk every day with each crew. Every morning the subject of the talk is emailed out to each foreman, who in turn fill out a form at the end of the talk confirming it has been presented. Then each worker in attendance signs the sheet.

Thomas funds an annual safety award. All workers without safety write-ups at the end of the year are entered into a drawing. Last year, the reward was $5,000 and this year it’s a weeklong trip to Florida for two.

As far as punishment for safety violations, Thomas says there are no penalties. The talks in the chair have been incentive enough to stay on the up-and-up, he says. In 2013, the company had no reported safety violations. Anything less is unacceptable for Thomas.

Lighting a candle

Thomas says it’s the quality of his 60 employees that sets Thomas Construction apart from the competition. “I look at character,” he says when discussing how he finds new employees. “All we have to have is someone with a willingness to learn.”

He prides himself on the longevity of his employees and assumes a clear role in their development and well-being. “When they land, they seem to stick,” Thomas says. “I think that’s what makes us different than other companies.” The keys to developing such employees: dignity and respect.

“They have a family, too,” he says. “If you can help them with their own goals in taking care of their family that’s dignity and respect. And the return for that is an honest day’s work,” Thomas says.

Even the way the company cares for its equipment has a lot to do with the comfort of the operators. “We try to keep our equipment looking good and looking clean. The seat is one of the most important parts of the machine. If the seat doesn’t work, if the heat doesn’t work and the air doesn’t work the operator is ticked off as soon as he gets in the machine,” Thomas says.

The company is in the process of developing an in-house training program in order to expand from within. “We can’t sit around an complain that it’s dark,” Thomas says. “We’ve got to light a candle.”

Looking back, looking forward

Thomas remembers a valuable lesson from when a major client went bankrupt. “I was afraid that I was going to lose my bonding because it took my cash,” he recalls. “We went to all the vendors and asked them to be patient. We didn’t get our cash but we did pay our vendors. When you work with people over the long haul and you hit a hard spot people will be patient with you.”

He also stresses learning how to properly manage people and understanding finance. “I was so interested in building things that I wasn’t paying enough attention to the financial side. Get a good accountant and a good attorney to mentor you through setting up the company right,” he says. “Get a good insurance person too. Bad things are going to happen, especially in the construction business.”

The key, Thomas says, is not growing too rapidly. “As long as I’m at the helm we’ll continue to grow a little bit each year. If you stop growing, you stagnate. I think the growth needs to be controlled though. You need to have the capital behind you so you can grow.”