As with concrete paving, stringless asphalt paving offers the benefit of eliminating the costly step of bringing in a survey crew to set up the stringline. Eliminating that step also removes the physical obstacles of the string and posts that get in the way of the paving crews and the workers running ancillary equipment.

But when we talk about stringless paving in asphalt, the conversation turns to 3D paving, which involves not just the 3D positioning systems, but also 3D machine control.

3D vs. 2D

In 2D paving, the action is about controlling grade. In 3D paving, it may include steering as well as automatic screed width control. The system works with a known 3D model, which specifies what grade and slope should be at a given point. In 2D, it’s more about setting up and paving away.

Systems for 2D paving consist of a single display, sonic sensor, contact sensor or sonic averaging beam. In 3D paving, the same components are there, but the 3D system talks to the 2D system so they work in conjunction.

“When you’re talking about 3D paving, people generally don’t understand what’s all involved,” says Nars Laikram, manager of commercial support and development for Vögele. He says 3D in this context is comprised of two factors: 3D job files and 3D paving. “When we say three dimensions, we are referring to depth, width, and direction. That’s the 3D. In that case, you have a job file that tells you at the x and y location, what the depth should be, and what the width should be.”

“3D systems communicate with a network of base stations that provide precise positioning data so the machines can work off a virtual design,” says Jon Anderson, global sales consultant at Caterpillar Paving. “The machines always have to maintain a line-of-sight to two base stations in order to precisely fix their position. Some urban environments can interfere with this, as can rural locations with heavy tree or brush cover. Usually, proper planning can ensure that the base station locations will not be subject to interference.”

In asphalt paving, you don’t necessarily need 3D control to drive the paver. You can get by with 2D machine control and just referencing off of sonics, especially with an averaging beam, and still get relatively smooth results, says Kevin Garcia, paving segment manager for Trimble. This is especially pertinent on projects where there’s no elevation specification, the top objective is ride smoothness, and material management isn’t a major concern. “If you don’t mind being a little bit high or a little bit low in certain areas, you can get by,” he says.

Contractor benefits

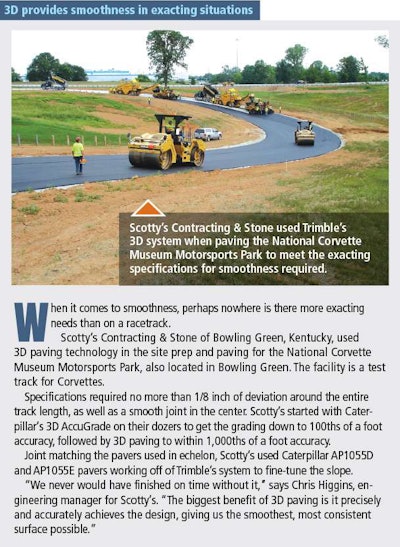

Where 3D paving excels and provides its biggest benefit is in accuracy, providing exact levels of smoothness and material management. The latter seems antithetical to what Garcia says about “getting by” with 2D paving.

“There are an increasing number of contractors who pride themselves on quality of work,” he says. “We see that list grow all the time, and machine control is a way for them to differentiate themselves at the bid table. With 3D machine control, you’re going to ensure that you hit minimum thickness of pavement without going over, which essentially is your yield. So, if you’re at the bid table, you can be very accurate with your tonnage, and therefore get your bid down. You are not having to put in as much fluff or overrun.”

While there are always early adopters for new technologies, Anderson says in most cases, contractors are using 3D systems to meet a specific challenge, such as exacting elevation or smoothness specifications, complex designs, or controlling material volumes. “It is still a bit of a specialty application—2D paving is more than adequate for the vast majority of work,” he says. “A lot of work is still paid by the ton.”

Contractors may also add 3D paving to their stable of services to offer value-added change orders, Garcia says.

It’s becoming more popular for contractors to submit a value-added change order after submitting a traditional bid, he says. Contractors can then go back and detail how many tons—and dollars—can be saved using 3D controls.

While there will be added costs using this approach, contractors can make it up in overall savings for the project. If, for example, the 3D machine control costs $50,000, but the contractor can save $250,000 on a project, then everyone wins, Garcia says.

Non-adopters

While 3D paving offers improvements in quality and time savings, contractors can balk at using it.

“There’s a fear of giving up that manual control and trusting that the automated machine control guidance is doing what it’s supposed to do,” Garcia says.

Cost can be a factor. There’s the additional cost of total stations, receivers, and perhaps fan lasers, all of which can cause contractors to balk. But in reality, Garcia says, the ROI on machine control systems is so quick that cost isn’t nearly the hurdle it used to be. “It’s more about the skill set of the crews in the field,” he says.

And contractors who do dirt work—where stringless controls have been proven performers—may have a leg up on paving-only contractors, since their crews already have that skill set.

“If a company also does earthwork, they may already have the infrastructure with their grade control systems on dirt moving equipment and the expertise to use it,” Anderson says.

Laikram posits one of the biggest challenges in the paving industry is the low number of contractors who understand the 3D side of things because they aren’t involved in the dirt work. “On the dirt side, however, you have contractors who have specialists employed,” he says. “Most asphalt contractors don’t do the dirt work themselves.”

Laikram sees this on the jobs he visits. In one instance, an asphalt paver subcontracted the stringline work. “That stringline probably cost them $50,000 to $75,000,” he says. “If they had had a 3D system, they could have plugged all of that into the 3D system and controlled the machine right off it.”

Moving forward

Increased adoption of 3D for paving contractors depends on strengthening specification requirements—some of which may even mandate 3D machine controls.

“We’re starting to hear states consider making machine control mandatory,” Garcia notes. “When that happens, I think we’ll see a lot of contractors adopt it. There are contractors who have embraced this technology wholeheartedly and use it extensively in their crews, but they are still the minority.”

Anderson says a contractor might see 3D paving as an opportunity to specialize in more challenging work and to be one of only a few who can offer the option as a competitive advantage. “There are considerable differences compared to standard 2D paving in terms of workflow, expertise, training and infrastructure,” he says. “But when the tolerances are tight, these systems are reliable and worth the investment.”

More contractors are adopting 3D machine control, Garcia says, adding: “To remain competitive at the bid table, and to ultimately put down the highest quality surface, they need machine control.”