Heavy Road Work

By Tina Grady Barbaccia

When energy companies began driving heavy truck traffic over rural Pennsylvania roads not built to withstand the weight, the state’s DOT charged a local contractor with rehabilitating and upgrading the road with a full-depth reclamation, cement stabilization project.

And the energy companies working to find natural gas pitched in and reached for their checkbooks.

The practice of deep well hydraulic fracturing – more commonly known as “fracking,” – is a way to tap into natural gas resources that the nation so badly needs. But the fracking process requires a heavy drilling equipment and a massive amount of water –5.6 million gallons for the typical Marcellus well, according to a May 2011 Chesapeake Energy fact sheet.

The wells are often located in rural areas. This means hundreds of truck trips carrying large amounts of fresh water to the jobsite and then additional trips to remove waste water from the drilling process. The roads for the heavy water trucks were not built to handle such heavy traffic.

In rural Pennsylvania, this heavy truck traffic on aging roads not designed for them, caused further road deterioration, according to local agencies. Energy companies with stakes in the Marcellus and Utica deep shale gas reserve development in that area decided to help pay for upgrades on the rural highways and secondary roads they needed to access.

Investment in State Route 1077 to was needed so that it could withstand the heavy truck traffic.

Asphalt and cement, take 2

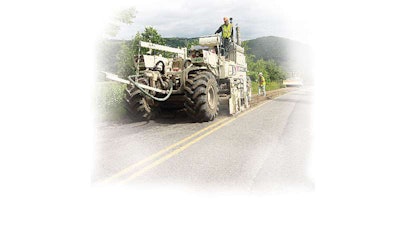

The family-owned Cortland, N.Y.-based Suit-Kote Corp. was charged with upgrading 45 miles of state highways, “farm-to-market,” and secondary roads. To rehabilitate the roads, Suit-Kote used full-depth reclamation (FDR) to dry grind the existing asphalt road as well as a portion of the sub-base material. A second pass with a reclaimer/stabilizer (a Terex RS600 and RS950) was then used to blend portland cement and water with the pulverized material to create a stabilized base for fresh asphalt. Prior to using the reclaimer/stabilizer on the road, Suit-Kote made 4-foot passes, 9 inches deep on both sides of the road. “All of this material was able to be saved and used later in the project,” Paul Suits, vice president of Suit-Kote Corp., tells Better Roads. “It was all nicely milled materials that we were able to use for shoulder backup and culvert material filling.

By re-using the asphalt that was dry ground and milled and putting it back into the mix, Suits estimates nearly $100,000 may have been saved.

Suits says his team dry ground the entire road 15 inches deep and then lightly compacted it. Suit-Kote then went back in and reground the road 15 inches deep. “On the second grind, we put cement in the road,” Suits notes. “We put in 120 pounds per square yard. We were putting cement on top of the road with special cement spreaders and grinding it through the road, then regrinding it.”

To properly reclaim the severely deteriorated road with the reclaimer/stabilizer’s 8-foot cutter – the RS600 has an 8-foot rotor and the RS950 has a 10-foot rotor – Suit-Kote’s crew made three to four passes over the 22-foot-wide road, with the 10-foot rotor saving them a pass. “We need to maintain the road’s proper grade and slope and not invert the road [by doing too few passes],” Suits says.

Bradford County, Pennsylvania, where the area of S.R. 1007 was rehabilitated, required an additional 4-foot slot mill step in front of the reclaimer/stabilizer. The slot milling is done so the new layer of asphalt doesn’t add too much height to the road, according to the Pennsylvania DOT. “When you do a recycling process by adding virgin material and cement, it tends to raise the profile of the road,” Suits points out. “We needed to keep it at the existing level or lower, and it’s the contractor’s responsibility to make the road passable to certain specs.”

Following the work done by the reclaimer/stabilizer, a padfoot roller provided preliminary compaction. This was followed by a grader, to establish grade for the new road surface. The grade at some points of the previous road surface had been as high as 12 percent, but the new road spec called for a maximum 6 percent grade, points out Mike Rodriguez, Terex Roadbuilding district manager. A smooth drum roller was used to finish before doing the stabilization. After a nearly five-day curing period, an average of 5 to 8 inches of asphalt was paved over the stabilized base material. Even with high truck traffic used in fracking, “the rehabilitated roads have a 10-year service life,” says Suit-Kote foreman Jeff O’Shea.

LESSONS LEARNED

As with any project, there are takeaways and challenges. “If you don’t learn something every day, there is something wrong,” Paul Suits says. “Everyone needs to understand what needs to be done going into the project. It makes it a much more successful project.”

Suits says coordinating with subcontractors and any other parties invested in the project is not a luxury but a necessity. “Nothing is perfect,” he says. “You might run into situations from time to time so you need to be able to work through them together.” Flooding sparked challenges for Suit-Kote and emphasized the importance of working together with everyone on the project, Suits says. “We had a lot of challenges because of all of the flooding,” Suits says. “It stressed us on the logistics for the transportation and being able to complete all of these roads.”

During the entire grinding and regrinding process, certain water percentages had to be maintained, creating yet another demand that had to be addressed and was critical to the job. “This was challenging throughout the summer because we had to add more water when it was cooler and less when it got warmer,” Suits says, adding that as temperatures varied throughout the day this required constant monitoring. “[This is why] it’s important to have a positive working relationship with everyone.”