Conventional wisdom has it that skid steers rule on hard surfaces and in tight quarters. Hard surfaces chew up expensive treads on compact track loaders, and confined spaces make other machines look like drunken bulls compared to skid steers’ nimble nature.

Is that enough to keep skid steers in your fleet? Maybe, maybe not. But skid steers are versatile and offer a host of appealing features.

“Skid steers are good at lift-and-carry,” says Eric Dahl, Bobcat loader product specialist. “They’re good for applications that tend to be less demanding. And they have a great balance of traction and travel speed that make them effective at snow removal.”

More “new” than meets the eye

Look at a skid steer from 2017 and one from 30 years ago, and there isn’t a lot that jumps out as new and improved. Other than the addition in the 1980s of vertical lift to the machine’s original radial-lift architecture, it might seem the design has stagnated.

“With the electrohydraulic system monitoring the machine’s travel speed, the Speed Sensitive Ride Control system on Cat skid steers can automatically engage when the machine reaches its activation speed,” says Kevin Coleman, skid steer loader product expert at Caterpillar. “The system automatically disengages at travel speeds below the activation speed to provide maximum digging and load placement performance.”

Kevin Scotese, Volvo skid steer product manager, says one of the most significant changes in the skid steer market is the ongoing move to larger machines. “These larger machines have more engine power and more hydraulic power, giving them greater lift capacity and lift height. In many cases, this allows a customer to consider replacing a compact wheel loader or backhoe loader with a skid steer. And that increased power means the larger skid steers can run bigger attachments and a wider range of attachments.”

Has horsepower become meaningless?

Tier 4 Final has different emissions standards for machines of less than 75 horsepower than for those of 75 horsepower and above. One result is that the cost of emissions compliance rises with the higher-power engines. This is true not only with the upfront cost of more extensive aftertreatment systems, but also with the ongoing cost of diesel exhaust fluid (DEF). This has caused a split in the market, and customers accustomed to choosing skid steers based on rated horsepower may have to develop a new strategy.

JCB is one of the manufacturers choosing to run lower-horsepower engines to stay under that 75-horsepower break. “Before Tier 4 Final, our most powerful skid steer was rated at 92 horsepower,” says Tinley. “Now our biggest model, the 330, is rated at 74.3 horsepower. But by reconfiguring the torque characteristics of the engine, the 330 delivers more performance than its predecessor did.”

Changes to hydraulics are often made. “We right-size the plumbing,” says Bill Wake, ASV director of product development, “which usually means going bigger. We can customize valves for a specific model. In general, we increase the performance of the hydraulic system to get increased performance.” He cites the company’s VS-75, which is rated at 74.2 horsepower and 192 pound-feet of torque. “It has higher available flow, 30.9 gallons per minute compared to 26 gallons per minute for its predecessor. And its rated operating capacity (ROC) is 3,500 pounds at 50 percent of tip, whereas its predecessor had a 3,000-pound ROC.”

Dahl says, “It’s really never been about horsepower. It’s always been about torque. And at least with Bobcat products, torque has been maintained or even increased as horsepower has slipped under the 75-horsepower mark.” He says a better benchmark is ROC, which tends to matter more to skid steer operators. “The opposite is true with CTLs, which do more pushing and emphasize horsepower. But with skids steers, ROC rules.”

Why is ROC the key spec? “Most skid steers will be doing lifting and material handling,” says Brent Coffey, loader product manager at Wacker Neuson. “Once a customer has decided on an ROC class, the next step is to understand what features are required. Skid steers have evolved as universal tool carriers as much as they are loaders. For example, if a customer needs high-flow hydraulics, the skid steer has to have the horsepower to run those hydraulics.” He says manufacturers strive to ensure the engine, hydraulics and electronics complement each other to provide the intended performance level. “Customers no longer have to worry about horsepower. That work has already been done for them.”

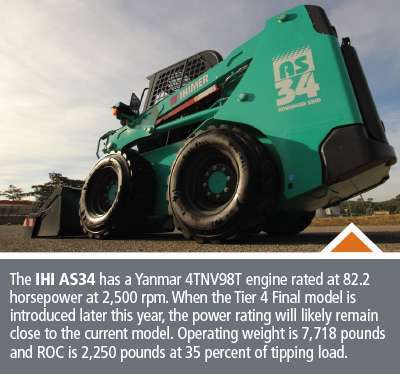

IHI is one of the few OEMs still making the transition to Tier 4 Final. It’s using manufacturer credits to sell through its remaining Tier 3 machines with an eye to being full Tier 4 Final by the end of 2017. Of its two skid steers, the AS34 is the one above 75 horsepower at 82 horsepower. “That machine will likely stay at its current power rating, but with a new Tier 4 Final engine,” says Kauffeld. “I can’t say for sure because we don’t have a Tier 4 Final model in North America at this time.”

Deere is also holding the line on horsepower and has even increased it on G Series machines. The 330 G has 91.2 gross horsepower and a 3,000-pound ROC, and the 328 has 82 gross horsepower and a 2,750-pound ROC. The weight of the machines is partly why Deere chose not to drop power, Zupancic says. He also notes it’s had requests for a model with big-machine performance, such as an 11-foot lift height, with less than 75 horsepower and therefore a simpler emissions control system. “We’re working on that, starting with adjusting the torque curve of an existing engine that would power the machine.”

Brad Wenger of New Holland Construction Equipment says some customers simply need more than 74 horsepower. “If you’re satisfied finessing your way through the day, then stay with the lower power ratings. But if you want to power through a hard dig, and you have a lot of digging to do, you really want the 90-horsepower machine.” As for the DEF needed for selective catalytic reduction aftertreatment on higher horsepower machines, “it’s nothing new and customers shouldn’t be afraid of it.”

Versatility equals appeal

Skid steers aren’t going away. They’re just being more clearly defined, and part of their definition is as prime movers for a host of attachments, which makes them even more versatile and therefore more appealing.

“Skid steers make great attachment platforms,” says Michael Shebetka, product manager at Takeuchi. “Advances in electronics and hydraulics make them even better at this. One skid steer can run a cold planer, switch to a bucket to remove material and switch to a broom for final cleanup. A multi-function display allows the operator to tailor performance for each task. It’s all done easily, efficiently and with one machine.”

Similarly, customers are more clearly defining the nature of their work. If they do a lot of one thing, they pick a machine that excels at that application. Coffey offers an example. If contractors are primarily using the excavator end of their backhoe, when the time comes to replace that backhoe they can save money and possibly improve production by choosing a compact excavator instead.

But having done the analysis, many customers find they do some of everything, often in confined spaces, and the skid steer becomes the logical choice. “With a compact footprint and nearly infinite attachment options, the skid steer has established itself as an all-around work machine,” says Coffey. “Getting the right machine means understanding the size of the operating space, type of work being done and the attachments needed for that work and total cost of ownership.” While that may lead to an application-specific machine, it also may lead to the ever-ready multi-tasking ability of a skid steer.