In Part 1 & Part 2 of this series we covered the definition and importance of management walkarounds as well some advice on how to conduct them effectively. In this last article of the series we’ll look at some additional implementation tips and challenges and conclude with a summary of the overall process.

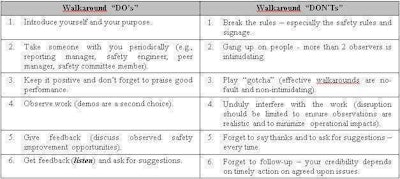

Do’s and Don’ts

There are several factors work observers should remember to include, as well as some factors to avoid, during any walkaround. Table 1 lists some of those I’ve found most critical.

Keeping it going

Like anything worth doing, management must maintain its commitment and provide ongoing leadership to ensure long-term success. Good intentions are not enough. The author’s experience suggests a minimum set of management actions to ensure continuing walkaround effectiveness.

- Expect Full Participation: This means holding managers accountable for performing routine – and high quality – walkarounds. Non-management walkarounds (e.g., safety committee members) are generally voluntary and best promoted by visible appreciation and use of observer feedback as well as some reward/recognition for participation.

- Establish Goals and Metrics: Develop both individual and organizational objectives as well as measures for evaluation of the program.

- Measure Performance: Accountability (for anything) is not possible unless you monitor performance. Potential metrics include: the number walkarounds performed, number of safety improvements generated, timeliness of corrective actions, and employee satisfaction with the program.

- Make Walkarounds an Integral Part of the Overall Safety Effort: Walkaround information is too valuable not to share. Several companies I’ve worked with, including DuPont and the Tennessee Valley Authority, made sharing walkaround information a principal part of their regular (at least monthly) management safety meetings. At these meetings each manager describes what he or she has found during recent walkarounds (good and bad) to peers as well as next level management. This not only informs management of safety performance in the field, it provides an opportunity to identify and correct organization-wide issues as they are reported up the chain. These discussions are also an important accountability tool. No manager wants to look unprepared or ineffective to his or her peers – and certainly not to the boss.

Challenges

Although the walkaround concept is relatively simple, implementation and sustainability, have their challenges. In my experience, there are several such challenges that should be expected and prepared for to ensure successful implementation.

- Motivating Managers: Nothing motivates managers like accountability. Anyone expected to perform walkarounds, however, should also be convinced via training and organizational communication of the value of walkarounds to their personal success, as well as to the continual improvement of the organization as a whole.

- Finding the Time: Most managers are very busy folks and are hard pressed to add yet another new thing to their already overloaded plates. Since good walkarounds do indeed call for some expenditure of scarce management time this is a genuine challenge. However, when pressed, managers often find less value-added activities (e.g., compliance inspections) that are expendable in favor of walkarounds.

- Doing Them Right: Some managers apparently just aren’t comfortable interacting with their employees about safety. In my experience, these managers quickly drift from making work observations and discussing them with their employees to performing low-value workplace compliance inspections. The walkaround effort must include sufficient review and accountability to ensure that the tendency to look at things and/or specific behaviors does not come at the expense of a deeper look at the safety of the work as a whole.

Summary

Managers have an obligation to understand how safely the work they are responsible for is performed. Lack of such an understanding has been a recurrent and principle factor in recent tragedies from the Columbia and Challenger disasters to the Deepwater Horizon and Texas City Refinery debacles. A genuine understanding of safety performance cannot be achieved from behind a desk and cannot be delegated. Nor can this understanding be gained through traditional compliance inspections that focus on conditions or some predetermined subset of behaviors. A deeper understanding of the work, and the systems and processes that support it (or not), is needed and should be the principle goal of work-focused walkaround programs.

Many organizations, such as DuPont, consider walkarounds the single most important activity their managers can do to promote safety. Walkarounds are not, however, a silver bullet. They are most effective in an overall safety effort that is managed like any other essential organizational objective. If safety isn’t addressed in a successful management framework (e.g., plan, do, study, act), any activity, regardless of its value, is likely to fail. With an effective management system andcommitment, however, management walkarounds are a proven method to help bring exceptional safety results to any organization.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on on the Safety Cary blog and has been republished with permission.

Loud’s more than 40 years of safety experience includes work with the Tennessee Valley Authority and Los Alamos National Laboratory. He is a regular presenter at national and international safety conferences and the author of numerous papers and articles. Mr. Loud is a Certified Safety Professional (CSP), and a retired Certified Hazardous Materials Manager (CHMM). He holds a BBA from the University of Memphis, an MS in Environmental Science from the University of Oklahoma and an MPH in Occupational Health and Safety from the University of Tennessee.