Workers pour concrete on a roadway in Highlands Ranch, Colorado, for one of the largest concrete pavement preservation projects.

Workers pour concrete on a roadway in Highlands Ranch, Colorado, for one of the largest concrete pavement preservation projects.Life-cycle analysis (LCA) is emerging as a leading method of determining the environmental impact at both a macro and micro level in transportation projects in context of sustainability. The concrete pavement industry in particular is pushing for the increased use of this approach.

LCAs, which are broadly used in Europe and are included in “green” construction regulations in some countries, look at factors from the material being used, including aggregate, to the end of a pavement’s useful life. Everything in the process is considered, such as purchasing raw materials, material processing, manufacturing, construction and the use of a pavement.

The process is limited in use within paving, but interest is growing. The Life Cycle Analysis 2017 Symposium in April at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign focused on LCA for pavements, with the primary objective of reviewing industry use of the plans, pulling together a consensus of use and determining ways to implement LCAs.

“This was a great opportunity to see how pavement LCA is gaining wider acceptance,” says American Concrete Pavement Association (ACPA) Technical Services Engineer Eric Ferrebee, who participated in the event. “The symposium also provided a view of the practical, meaningful ways industry, the public sector and academia are working together to show the importance and value of LCA in highway, airport and roadway construction.”

ACPA Executive Vice President Leif Wathne also participated in a panel discussion, stressing that “meaningful advancement in sustainable practices and LCA will only be realized by fully marshaling and leveraging the expertise, know-how and innovative spirit of both paving industries, primarily through competition.”

According to the Federal Highway Administration’s Pavement Life Cycle Assessment Framework, released last July, the most common uses of LCAs for pavements in North America include:

• Selecting a material or pavement structural design.

• Evaluating the impacts of potential changes in a policy or specification.

• Developing LCA tools for screening or detailed LCA for the scoping or design of a project.

• Evaluating scenarios for network-level decisions and strategies for preservation, maintenance and rehabilitation.

• Developing material environment product declarations for pavement applications.

Quantifying sustainability

The other three are performance assessment, life-cycle cost analysis (LCCA) and sustainability rating systems.

Performance assessment covers how a pavement performs compared to its “intended” purpose in relation to current standard practices. This would look at materials used or method of construction and how they compare to other methods considered standard with respect to longevity of a pavement’s service life.

A life-cycle cost analysis looks at the costs of a project to determine the economic impact of sustainable practices. LCCAs do not address environmental issues or “livable community conditions” of a project, which FHWA cautions could be difficult to determine or could “double count” what’s also measured in an LCA. The agency prefers LCCAs be used as a tool to support project decisions, and it recommends its RealCost program in processing LCCA data.

Sustainability rating systems list construction practices or features of a project that affect sustainability and measure the impact of these factors.

“In its simplest form, a rating system may count the implementation of every best practice equally (e.g., all worth one point), in which case the rating system amounts to a tally of the number of best practices used,” says the Pavement Life Cycle Assessment Framework. “In more complex forms, rating systems weight best practices (usually in relation to their impact on a selected definition of sustainability or a selected set of priorities), which can assist in choosing the most impactful best practices to use given a limited scope or budget. Many national and international pavement sustainability rating systems are currently available (e.g., INVEST, Greenroads, and Envision).”

Materials and sustainability

Longevity is a sure test of a sustainable pavement, and this measure is driven by the materials used, both recycled and new.

The CP Tech Center recently surveyed concrete pavement companies about the use of RCA, offering a look at 26 contractor firms in 19 states. The firms represent about 18 percent of the national volume of concrete paving for 2014 through 1,063 projects.

Fourteen of the firms outsource their recycling, while six did their own, and five did a combination of both. A little more than half reported that at least 81 percent of their projects included removal of pavement, which would then be recycled. Granular subbase was the most often cited use of RCA, at 42 percent. Another 16 percent reported RCA was crushed product for other markets, 15 percent was used for granular shoulder and other crushed products related to pavement, 14 percent went toward concrete aggregate use, and 12 percent was used on embankments or was wasted.

Historical concrete pavements

It’s hard to argue the longevity of concrete, as we marvel at the Roman structures scattered across Europe that have withstood millennia. And while we don’t have such a lengthy historical perspective in the United States, there are a number of concrete pavements that have withstood decades of use and abuse.

The ACPA is creating a storehouse of old concrete pavements, with their first step being the creation of the Historic Concrete Pavement Explorer website last year. The map-based, mobile-friendly site provides details on these pavements, with potential for photo galleries, technical details and historical context.

“The website represents ACPA’s commitment to the Task Force on Preservation of Artifacts from Historical Concrete Pavements,” says ACPA President and CEO Jerry Voigt. “The task force is working to document concrete pavements and collect photographs and other artifacts for concrete pavements that are 75 years or older and/or which represent ‘firsts’ and other significant milestones throughout history.”

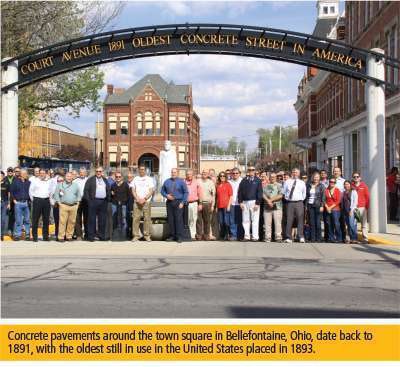

The launch of the site roughly coincided with the 125th anniversary of the country’s first concrete pavement, placed in 1891 in Bellefontaine, Ohio, by George Bartholomew and WTG Snyder. That original pavement is no longer in use; however, pavement that was placed around the town square just two years later remains. It has undergone some rehabilitation, including full- and partial-depth concrete patching in 1962, the early 1990s and in 2007.

This pavement was considered an engineering marvel at the time. So much so, that a section of the concrete was on display at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and won first place for Engineering Technology Advancement in Paving Materials.

On July 12 this year, the ACPA, the City of Bellefontaine, the Ohio Chapter of the ACPA and the Task Force on Preservation of Artifacts from Historical Concrete Pavements held a celebration to commemorate an 11-foot replica of the original 7-foot-wide test strip of the 1891 pavement.

“The test strip is part of a reconstruction project in downtown Bellefontaine, and it’s a big deal to our industry and to Bellefontaine,” says Bill Davenport, ACPA vice president of communications. Shiraz Tayabji, with Advanced Concrete Pavement Consultancy and one of the project leaders, said the re-created test strip “will provide service for another 100-plus years, linking the past, present and future of the concrete pavement industry.”

But while Bellefontaine is definitively recognized as the site of the oldest concrete pavement in the country, no absolute ranking is available. Davenport recently polled ACPA chapters, and through their submissions, the following list gives a snapshot of some of these long-lasting pavements:

1906 – Portland Street, Calumet, Michigan

1907 – Van Buren, Arkansas

1907-1909 – County road in Mahaska County, Iowa

1908 – Grand Forks, North Dakota

1909 – Cemetery Road, Eddyville, Iowa

1909 – 6th Street, Duluth, Minnesota

1910 – Multiple city streets, Grand Forks, North Dakota

1912 – Central Avenue, Urbana, Illinois

1913 – Dollarway Pavement, White Hall, Arkansas

1914 – Belknap Place, San Antonio, Texas

1914 – Third Street, Delevan, Illinois

1914 – River Road, Moscow, Iowa

1915 – “Original seedling mile,” Grand Island, Nebraska

1916 – Westminster Street, Salt Lake City, Utah

1916-1927 – Multiple city streets, Fort Collins, Colorado

1918 – County road in Woodbury County, Iowa

1919 – Sunset Highway, Spokane, Washington

Belknap Place in the Monte Vista Historic District of San Antonio was honored with ACPA’s 2016 Lifetime Pavement Recognition award, commemorating it as the oldest concrete pavement in Texas. It was created using a process called “Granitoid,” a two-lift system that features coarse aggregate in the bottom lift and hard granite aggregate in the surface course. Cars, trucks and buses continue to travel across this pavement, and officials say there are few signs of faulting or deterioration.