In Minnesota, Shafer Contracting has been installing unbonded concrete overlay over concrete projects on Interstate 35, using nonwoven geotextile fabric as a separation layer.

The Shafer crews are among a rising tide of contractors and state DOTs turning to nonwoven geotextile fabric as an alternative to hot-mix asphalt separation layers for unbonded concrete overlay over concrete applications (called UBCOC).

For many years, contractors used asphalt as an interlayer to separate, drain and provide a cushion layer for the new concrete overlay, he says.

Now, many states use geotextile separation layers routinely, while others are considering the practice, according to the National Concrete Pavement Technology Center (CP Tech Center) at Iowa State University, with which Harrington has long been affiliated.

So far, geotextile separations have been used on more than 10 million square yards of concrete overlays in the United States.

In fact, the majority of unbonded concrete overlay projects are now incorporating or considering the geotextile fabrics as a separator layer to prevent reflective cracking, enhance drainage and provide cushioning, Harrington says.

Using the permeable fabric in overlays rather than a one-inch layer of asphalt saves contractors and state agencies time and money, he and other experts say. It’s an application that’s easy to learn, and state highway departments such as the Minnesota Department of Transportation are researching how to optimize use of these fabrics.

“It’s about half the cost typically, or less, than an asphalt interlayer. It’s relatively quick to put down, and you don’t have to bring in an asphalt contractor to a concrete project,” Harrington says.

“A fabric drains better than asphalt,” adds Harrington, co-author of the Guide to Concrete Overlays manual. “It’s a material that wicks away water.”

Minnesota has adopted geotextiles for widespread use. More than 3 million square yards of nonwoven geotextiles have been used in unbonded concrete overlays in the state since 2010, according to Matt Zeller, executive director of the Concrete Paving Association of Minnesota.

“It saves time, so therefore, it saves money,” agrees Blake Nelson, MnDOT technologies engineer. “It just goes down so much faster than any other means or method. You can cover a lot of area with these fabrics in a hurry.”

The fabric cost is nominal, with MnDOT seeing bids that are “a couple dollars to a few dollars per square yard,” he says.

A contractor’s view

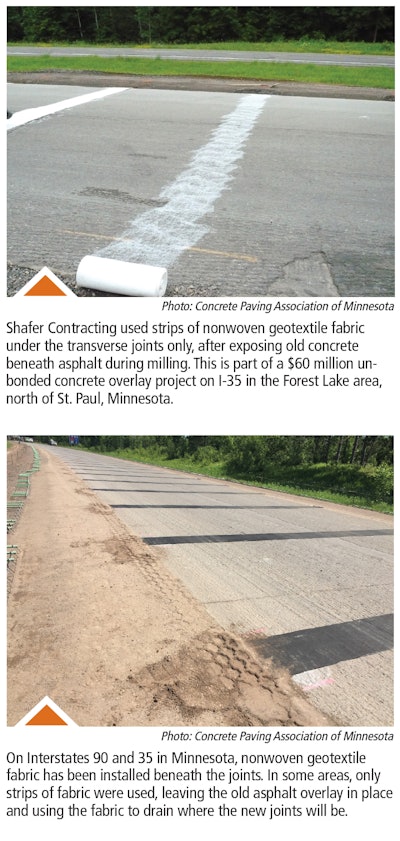

While geotextile fabrics are typically unrolled over an entire lane, MnDOT has taken a different tack on some unbonded concrete overlay over asphalt projects, specifying that crews place strips that are only 15 to 18 inches wide under transverse joints.

That’s been the application for Shafer, a prime contractor in two major concrete and bridge overlay projects on I-35 north of the Twin Cities. These are the ongoing $60 million Forest Lake area project and another to the north, the $24 million “Snake River” project in the Pine City-Hinckley area, says Greg Pelkey, Shafer vice president.

Crews have placed the material under transverse joints, “so when the water flows through the cracks or the joints down to the base, the geotextile fabric acts like a wick and wicks it out to the outside edges of the road,” Pelkey says.

The fabric extends beyond the edge of the concrete pavement, he explains.

The other major benefit – preventing reflective cracking – led to a different application for Shafer crews working on the six-mile project of I-35 in the cities of Lino Lakes, Columbus and Forest Lake.

That $60 million project, set for completion in 2019, includes installing a concrete overlay on existing asphalt that was atop old concrete pavement, along with three new bridges.

“When we milled the asphalt to correct for the cross slope before we paved,” Pelkey says, “we ended up running into the underlying concrete pavement.”

MnDOT engineers realized that with the existing asphalt working as a stress relief layer for much of the roadway, they could put down less fabric as an interlayer, and only where needed, for their concrete overlay, says Pelkey.

“It would work as a stress relief layer, so the underlying cracks in the pavement below don’t reflect through,” he says. “And it also drains the water away from the underlying pavements.”

Throughout the rest of the projects, rather than spending the money to place the geotextile fabric under the entire roadway, Pelkey says, crews installed the bands of geotextile that are 15 to 18 inches wide. Contractor PCi Roads of St. Michael, Minnesota, was also involved.

Dowel bar assemblies

Between the transverse contraction joints, each panel on the roadway is 15 feet longitudinally and 12 to 14 feet across the road, and they act as separate panels.

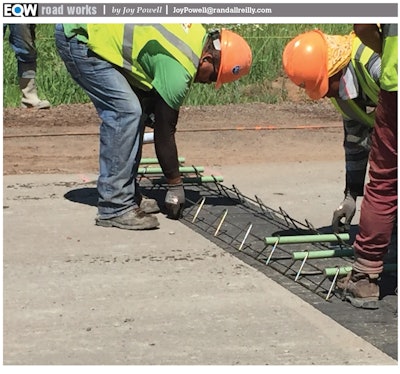

The crews installed the geotextile fabrics at the transverse contraction points under dowel bar assemblies.

The dowel bars carry the load on the roadway from one panel to the next. The dowel bar assemblies, or baskets, were placed in the transverse contraction joints on top of the textile. “The basket anchors down the geotextile to the underlaying pavement and surface so it doesn’t move,” Pelkey explains.

The baskets secure the dowels – the short steel bars that connect slabs without restricting horizontal joint movement. This can help prevent the faulting, or “steps,” that can occur during a pavement’s life, according to the Federal Highway Administration, which works closely with the CP Tech Center.

Application

For jobsites, the fabric typically comes in black or white rolls, often 12 or 13 feet wide – the width of most lanes.

If you’re looking at a two-lane interstate with two lanes on each side of the median, your total width might be between 24 and 27 feet, Zeller says.

“On some jobs, you may end up with 8-foot-wide rolls to do a shoulder and 12- or 13-foot-wide rolls to do the main line,” he explains.

Shafer crews have been using an industrial glue and have also used a hot-pour sealant on large sheets on another job, which works well, Pelkey says. “We could drive trucks across the geotextile fabric and have turning movements on it, yet it wouldn’t move the fabric at all.”

Batch trucks, for example, hauled across it, as did related traffic, but the glue adhered well, Pelkey says. You can also pin the fabric to the ground with nails and washers, he adds.

Sometimes workers manually unfurl the rolls, and some firms develop home-made systems for the application.

“They use different paving machines or compaction machines, or in the case of a mill and overlay, the milling machines behind those,” says Nelson. “It could be any kind of machine. Some may just use a front-end loader and mount it on there and be able to drive and unroll it that way.”

He’s seen contractors take buckets off their loaders and put on a mounting bracket to lift and deploy rolls.

“They adapt to whatever equipment they have available out there, so it really varies from contractor to contractor,” Nelson says. “They’ll find a way, mount it on their machines and away they go.”

Fabric versus asphalt

What are the other jobsite benefits of using geotextiles as an alternative to a layer of asphalt?

“The nice thing about it,” Zeller says, “is for a lot of the concrete paving contractors, it’s an operation they do in-house. If they were going to use an asphalt separation layer, they’d have to get another contractor to do that work.”

Getting another contractor to do part of the work adds to the complexity, he says. “You can end up having conflicts of equipment and operators and trucks; whereas, when it’s in-house, it’s an operation they do with their crews.”

In addition, using fabric instead of asphalt as a separator layer can minimize how much height you need to add for an overlay, which can increase costs in more ways than one, Zeller notes.

While asphalt might raise the surface 1 to 2 inches, the fabric will raise it around a quarter inch. For each inch the pavement is raised, shoulders also have to be adjusted. Abutting roads have to be matched, along with making sure there’s enough vertical clearance for bridges – all of which can increase application time and costs, Harrington and Zeller say.

Zeller elaborates on how a fabric interlayer application can enhance drainage:

“On a lot of our designs, the designer will put an edge drain – a trench drain – right along the old edge of the concrete, under the new concrete, and they’ll run that fabric down into that trench drain. If any water gets between the two layers of concrete, it’s going to drain right into that trench drain and then out into the ditches.”

Water in concrete or asphalt expands when it freezes, and most of the fabric installations are being carried out in the Midwest to help address that, Zeller says. As a road gets cold, it shrinks and the joints or the cracks get wider as the panels of asphalt or concrete shorten. That can cause pavement to crack and break up.

Southern states can experience heat-related pavement issues that fabrics may help, Zeller says.

“The concrete’s going to move relative to a high temperature, so it’ll expand a little yet still provide drainage characteristics,” he says. “They may not have the freeze problems, but saturated concrete and saturated asphalt can be an issue because they soak up the water and can become a problem.”

Moving forward

So how to get started using geotextiles in your paving business?

“I would say, like anything new, start small,” advises Zeller. “Start off and learn and ask for help. The manufacturers of the fabric are really good resources.”

Go to conferences, he suggests, such as the American Concrete Paving Association, as well as those at the state level, such as in Minnesota.

And for those jobs using continuously reinforced concrete with steel, Zeller recommends that roadway owners have contractors “put fabric on there as kind of a belt and suspenders to make sure we do separate the two layers – and the concrete gets to work as an independent layer.”