From experts’ recommendations on best practices to investing in tools such as intelligent compaction, there are ways to ensure consistency and high performance in the base course.

“If we don’t have a good base structure to start with, we’re not going to have a good, sturdy surface material,” says Tim Kowalski, an application support manager for Hamm, a Wirtgen America brand.

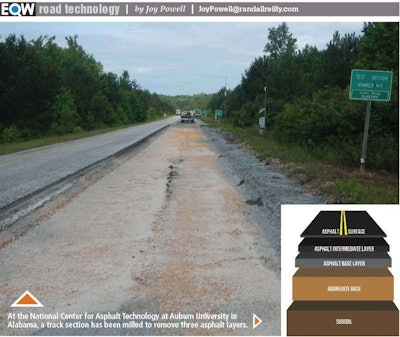

Photos and graphic illustration courtesy of National Center for Asphalt Technology at Auburn University in Alabama.

“It’s very critical you have the right moisture content in the material so that you can compact all the material in a manner that is going to have a good, stable base and good load-bearing capacity,” Kowalski adds.

“A properly designed and installed base is an important component in achieving optimal performance of the pavement structure,” agrees Brett Williams, director of engineering and technical support for the National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA).

“As with any construction, the strength and stability of the foundation – in this case, the road base – provides a solid platform for what is built above it.”

Williams recommends three best practices:

• Make safety a core value and ensure good safety practices in all facets of the business.

• Incorporate continuous quality improvement principles and practices into a robust quality program.

• Provide efficient communication internally, with customers and with the public.

Michael Heitzman, assistant director at the National Center for Asphalt Technology at Auburn University in Alabama, defines the base layer as the material typically just beneath the pavement before you get to the subgrade.

Most U.S. roads are already in place, and that determines how much you can do with the base, he says.

“We have to recognize the characteristics of the existing base as we do the renovation or rehabilitation of the pavement, because we simply can’t lift the pavement up, change the base and put the pavement back down,” he explains.

That can mean living with the limitations caused by the existing base.

“If the base and drainage are the primary factors that are causing the damage to the pavement, we have to address those, and there are some techniques for that,” Heitzman says. “That’s part of doing the forensic studies – when we’re going back out to try to improve an existing pavement.”

From the contractor’s perspective, best practices begin with meeting criteria and specifications from the agency or owner, he says.

Agencies use base courses in a variety of ways. He notes that agencies in the Southwest, for example, typically use a lot of aggregate and place a fairly thin asphalt pavement. Other states may use little base aggregate with a thicker asphalt pavement on top.

Another critical factor is that, depending upon the characteristics of the subgrade, “we want that base to be able to carry water away from the subgrade, because if our subgrade gets soft, then we lose part of our pavement structure,” Heitzman says.

If the agency is specifying a drainable base, the amount of dust or fine material in the base aggregate will be relatively small. Other agencies without a drainage problem may use more of a crushed, full gradation base that’s tighter, because it has much more fine material in it, Heitzman explains.

Agencies desiring a more drainable base may use a treated base, which means they’ll add a low amount of cement paste or asphalt binder in the aggregate to help hold that aggregate base together. This gives more structural value while maintaining drainage characteristics.

A best practice in some areas is using crushed aggregate rather than river-run gravel as base material for strength and drainage, Heitzman says. “It provides a better platform for the pavement to sit on; because of its angularity, it’s much stronger.”

Heitzman says another best practice focuses on adequate drainage. The cross slope on the subgrade becomes critical, because if you do plan to use the base to carry water away, then you’ve got to have a reasonable slope on the subgrade so the water will travel.

Contractors use equipment to trim the subgrade to a specific line and grade and put a proper cross slope on the subgrade before the base rock is placed on top.

“That way, you know that you have the cross slope, which might be in the 2 to 4 percent range as far as the amount of slope,” Heitzman says. The greater the slope, the better, but then you’ve got to put in more crushed base, he notes.

Is the industry consistently using best practices?

How much the industry actually uses “best practices” is an issue of increasing importance, especially given our nation’s crumbling infrastructure.

“Best practices are used when the owner or agency requires them. They may or may not be used if the industry is left on their own to apply them,” Heitzman says.

“If, in fact, their practices are reducing the strength of the base, or reducing the strength of the subgrade, then in theory the pavement will not last as long.”

At the roadbuilding firm Colas, Technical Director Jean-Paul Fort works to ensure quality, which he defines as meeting specifications consistently at the best cost.

“The big challenge is to stay within those limits and be as efficient as possible to achieve profitability,” says Fort, who is based in Cincinnati. “Best practices allow you to control production costs and achieve quality in the most efficient way.”

Jeff Wunderlich, a paving contractor with North Valley Incorporated in the northern Twin Cities metro area, notes that while it’s critical to get the base right, quality takes time.

“You’re making the road 60 percent better every time you go over it. So, if you can make the bottom right, the top will be better,” Wunderlich says.

“We build everything in our company from the ground up. I pave the bottom just the same as I do the top. I use the skis. I roll it the same. We try to make the bottom as smooth as the top we want. It just keeps getting better.”

Whether a contractor uses best practices will show in the top layer, Wunderlich says.

He hears from some inspectors about contractors who won low bids and “are going to go really fast.” That’s versus a company that goes slower to maintain quality, Wunderlich says. The upshot is that agencies looking for the lowest bids might not get a contractor using best practices, he says.

The problem is, there are some customers who don’t want to pay for the extra time to ensure the base is put down with best practices, contractors say.

“I always say the low bid isn’t always the best bid, but that’s the system we have today,” says Tim Kowalksi, application support manager for Hamm, a Wirtgen America company. He doesn’t like the term “best practices” because it is vague and differs from firm to firm. He prefers the term “suggested procedures.”

“In some specifications there are penalties if people don’t do at least what the specs ask them to do,” Kowalski says. “Some people get penalized more because they want to do something different to either get done in a faster way, or whatever. That’s just the nature of the business.”

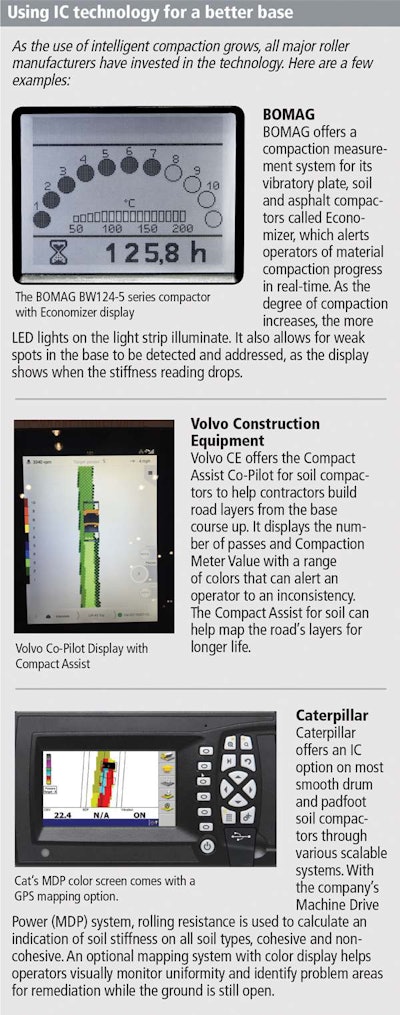

Using IC as a best practice for the base course

Kowalksi instructs contractors on intelligent compaction (IC), one of his “suggested procedures” for base courses. His presentations include one recently on “How to Use Compaction” at 2018 World of Asphalt and Aggregates Academy & Expo in Houston, where he spoke with Equipment World.

Base can be simple to deal with, but the processes become more complicated when you have time and temperature affecting compaction results while building asphalt roads, Kowalski says.

If the base has too much moisture, it’s tilled and recompacted. If it’s too dry, it’s tilled up, moisture is added, and it’s recompacted.

So, if you have a soft spot or other anomaly in base layers, address it. “Fix it before you put asphalt over the top of it,” Kowalski advises.

Intelligent compaction helps to identify those soft areas.

Sometimes, you can drive over new pavement and get a little bump over a culvert. “That’s because the base isn’t constructed right,” he says, “and asphalt isn’t going to bridge it.”