Older and newer: This older-style curb ramp contrasts with a late model in foreground

Older and newer: This older-style curb ramp contrasts with a late model in foregroundPavement preservation stakeholders in the United States are concerned that a reinterpretation of the Americans with Disabilities Act last year by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) will lead to disruption of low-cost pavement preservation programs in this country.

The technical advisory requires that curb ramps and other upgrades be mandated for a variety of thin pavement preservation surface treatments that heretofore had been defined as maintenance, and therefore did not require upgrades until alterations were made to the road.

This unfunded mandate could set the pavement preservation mantra of “the right treatment to the right road at the right time” on its head, with cost pressures resulting in the wrong treatment to the wrong road at the wrong time, or no treatment at all if the ADA curb ramp installation costs are too high.

But at the same time it could lead to a reassessment of an agency’s compliance with the ADA as the agency inventories which intersections need remediation, and which don’t, regardless of the status of its pavement preservation program.

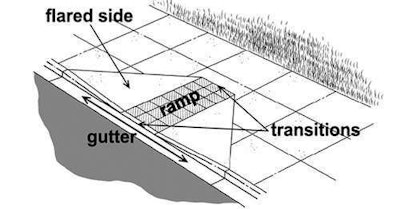

Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) requires that state and local governments make sure that persons with disabilities have access to the pedestrian routes in the public right-of-way. An important part of this requirement is the obligation that, whenever streets, roadways or highways are altered, curb ramps be provided where street level pedestrian walkways cross curbs.

Pictured is a regulation curb on a suburban street. An important part of this requirement is the obligation that whenever street, roadways or highways are altered, curb ramps be provided where street level pedestrian walkways cross curbs.

Pictured is a regulation curb on a suburban street. An important part of this requirement is the obligation that whenever street, roadways or highways are altered, curb ramps be provided where street level pedestrian walkways cross curbs.For decades, states, counties and municipalities should have “ADA plans” in place, thus have a program for providing curb ramps, in many cases installing curb ramps even without the trigger of pavement “alteration.” Programs for curb reconstruction to provide curb cuts without associated pavement reconstruction has kept these agencies ahead in the game.

During those same decades, the pavement preservation movement gathered steam, and now many preservation programs are in place at all levels of government, with pavement inventories and condition databases used to program preservation work. But, the new ADA guidance from inside the Beltway does not take the existing ADA plans into consideration, and the guidance creates contradictions in prioritizing ADA work and pavement preservation programs.

Preservation saves roads, money

Proponents maintain that pavement preservation techniques are cost-effective and environmentally sustainable strategies that extend the life of pavements before they deteriorate substantially. They add that pavement preservation is like changing the oil in your car, or painting your house: a smaller upfront investment avoids high future costs of reconstruction and rehabilitation.

For roads, these techniques include preventive maintenance surface treatments such as slurry surfacings, crack sealing, chip sealing, micro surfacing, surface rejuvenation, hot and cold in-place recycling, thin-lift hot-mix asphalt paving, and concrete pavement restoration.

Local governments now must recalibrate their pavement preservation programs to accommodate the cost of compliance or change strategies completely. An ideal curb ramp that meets ADA requirements is shown.

Local governments now must recalibrate their pavement preservation programs to accommodate the cost of compliance or change strategies completely. An ideal curb ramp that meets ADA requirements is shown.Pavement preservation methods prolong pavement life, says the National Center for Pavement Preservation (NCPP), avoiding high future costs of reconstruction or rehabilitation through the expenditure of lesser amounts of money at critical points in a pavement’s life. Experience shows that spending a dollar on pavement preservation can eliminate or delay spending $6 to $10 on future rehabilitation or reconstruction costs, NCPP says.

Previously, pavement preservation treatments weren’t considered road alterations that would trigger ADA requirements. But following the new guidance released last year, under the ADA, some pavement preservation treatments now require costly accessibility features such as curb ramps be installed as part of the project, while other preservation treatments don’t.

Projects now deemed to be alterations must include curb ramps within the scope of a project. These include micro surfacing, thin-lift overlays, open-graded surface courses, cape seals, mill-and-overlays, and hot in-place recycling.

Projects deemed to be maintenance, and exempt from curb ramps, include crack and joint filling and sealing, surface, chip, slurry, scrub and fog seals, concrete joint repairs and dowel bar retrofits, spot high-friction treatments, undersealing, diamond grinding, and pavement patching.

“This recent DOT/DOJ interpretation changing long-standing FHWA practices threatens to take away several cost effective maintenance ‘tools’ for government agencies,” said FP2 Inc. executive director Jim Moulthrop, P.E. “Our experience is showing that the right treatment, for the right road, at the right time, is put at risk by the new ADA guidelines, which can even lead to no treatment if it’s perceived that the right treatment would lead to unaffordable capital improvements. This is counterproductive to road maintenance programs achieving ADA goals, and flies in the face of the pavement preservation language of our federal surface transportation legislation, MAP-21.”

Survey shows California impact

That’s borne out by a survey this spring of local governments in California that shows the impact that the ADA guidance will have on local governments that now must recalibrate their pavement preservation programs to accommodate the cost of compliance, or change strategies completely.

The survey was conducted in May by Ding Cheng, Ph.D., and Gary Hicks, Ph.D., of the California Pavement Preservation (CP2) Center at the California State University-Chico. Nearly 260 road professionals answered – of whom 62 percent were from local agencies, and 25 percent from state or federal agencies – and the survey found that more than 63 percent of respondents believe the new interpretation of what is considered alteration and what is considered maintenance will greatly impact their ability to maintain their roads.

This ramp is present with friction treatment, but it lacks tactile bumps.

This ramp is present with friction treatment, but it lacks tactile bumps.Preservation treatments like micro surfacing, cape seals, thin and ultrathin HMA, and in-place recycling now are considered by the new rules to be alterations that will require curb ramps and amenities. More than 90 percent of respondents said they currently use these treatments, but 54 percent said they’d no longer use them in the face of the new ADA interpretation.

Would the new ADA interpretation lead to deferred projects? Some 65 percent of respondents said it would; 55 percent said it would increase the cost of roads by 20 to 40 percent, 34 percent by 40 to 60 percent, and 11 percent of respondents believe they will see 60 to 80 percent increases in their road costs.

Nearly 70 percent of respondents said the new ADA guidance will cause them to shift away from treatments that have worked well in the past, and 75 percent said it would lead to deferred maintenance.

“The new interpretation of what is considered as alteration and what is considered as maintenance will affect agencies’ ability to maintain roads,” Cheng and Hicks say. “Agencies may decide to no longer use surface treatments, such as microsurfacing, cape seal, or in-place recycling, if they require the installation of curb ramps. The technical advisory will cause agencies to defer preservation projects, and increase project costs by 20 to 40 percent or more.”

Transition plan will help

Regardless of the status of local agency pavement preservation programs, existing federal laws for years have required that agencies with authority over streets, roads or walkways to have developed a transition plan and complete structural changes like curb ramps by Jan. 26, 1995.

“If agencies have complied with these long-standing program access regulations, most needed curb ramps will already be in place,” said Doug Hecox, FHWA acting associate administrator for public affairs, as reported in California Asphalt Magazine. “The joint [technical advisory] addresses remaining barriers between sidewalks and streets to provide access to pedestrian facilities for more than 30 million people with disabilities based on the 2010 Census data.”

Thus whether they have preservation programs or not, agencies without their full complement of curb ramps and other amenities need a transition plan from their current state to a network that is fully accessible and ADA-compliant, says Steve Mueller, P.E., president, Stephen Mueller Consultancy in Colorado.

Mueller, who just launched his consulting practice after retiring as pavement and materials engineer for the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Colorado Resource Center, has a long history of involvement with pavement preservation, pavement recycling, and asphalt materials and construction. He also is a former district engineer for the Asphalt Institute, and pavement management engineer for Aurora, Colo.

“The law is designed to provide pedestrian mobility to everyone in our society,” Mueller tells Better Roads. ”Agencies need to understand how accessible their roads currently are, and develop a good inventory of ramps and other access features, such as sidewalk width and anything else needed to accommodate people who are physically challenged, and make the changes they need,” Mueller said.

Colored “truncated domes” or tactile indicators are required for citizens with vision problems, he said. “They are detectable with canes and by foot,” he says. “If a signal is present an agency would have to implement audible signals. The agreement between the DOT and DOJ said ‘if you are doing any alterations to the paving surface, the roadway must be made completely accessible.’”

Where the Sidewalk Ends: Makeshift asphalt ramp serves until surface or friction course of asphalt is placed in condo development.

Where the Sidewalk Ends: Makeshift asphalt ramp serves until surface or friction course of asphalt is placed in condo development.The issue then becomes which preservation treatments make for alterations, and which don’t. “Microsurfacing and slurry surfacings are close to the same product, except for polymer modification in the former,” Mueller says. “If slurry seals are a maintenance technique, and micro surfacing an alteration, it does not make any technical sense whatsoever. I am very concerned about the engineering principles that were applied in this agreement, and that the DOT decisions were taken at a high level without adequate technical involvement and review. When basic engineering principles are ignored, and basic materials aren’t well understood by the people putting these agreements together, the outcome won’t technically be what it should have been.”

Nonetheless, as a civil rights issue, compliance with the ADA is obligatory to all public agencies, Mueller says. “The lack of technical involvement doesn’t mean agencies shouldn’t be following the civil rights function of the law,” he says. “The law has been in effect for more than 25 years now, and many local communities – and some state DOTs – have not been complying with the law. Their attitude was that it was just another unfunded mandate, and they were ignoring the law and not creating the transition plan that should have been there. If the agencies had been doing their transition planning, this agreement might not have been necessary.”

Note: A guide to the requirements of Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act relating to curb ramps at pedestrian crossings may be found online in the DOJ’s ADA Toolkit: visit ada.gov/pcatoolkit/ch6_toolkit.pdf.

Not a federal funding issue

Also, the mandate being a civil rights issue means that it has nothing to do with whether an agency receives federal funds, said Robert Mooney, pre-construction team leader, FHWA, at the combined annual meetings of the Asphalt Recycling & Reclaiming Association, Asphalt Emulsion Manufacturers Association, and International Slurry Surfacing Association in February. “It applies to all entities: all agencies, all states, towns, counties, even if they are not recipients of federal funds,” he said. “If [your project] is not in compliance with the law, even though it’s not federally funded, if there is a complaint from a citizen you will be held responsible.”

Originally, the DOJ proposed that any preservation work other than a pothole repair was to be considered an alteration, requiring that accessibility be provided, he said. “To them, the only maintenance item was a pothole,” Mooney said. “That was our starting point.”

But in 2013 DOJ and DOT continued the dialogue, based on information from states and towns, contractors, and complaints about how unevenly the guidance was being enforced, Mooney said. The appearance was that preservation equipment was being utilized, but no curb ramps were being installed. “It was the Department of Justice’s point of view that if the public perception was that major work was going on a roadway, that we [would] need to address accessibility for all the public,” he said.

Mooney was asked what the ramifications would be for an agency that did not upgrade curbs. “[While] it depends on the exact scenario, a complainant – a citizen putting in a complaint – will be able to go to court and sue, and they would most likely win,” Mooney said. “The agency would be held responsible in the lawsuit.”

He also said that if FHWA found that an agency was not in compliance, it could withhold funds for unrelated projects until the project in question had been rectified. “If we get wind of it and find there is truth to it, other projects could be affected,” Mooney said. “They can withhold funds for Project B until Project A is handled properly.”

Toward a sensible solution

There is no easy way out of the predicament, experts close to the situation say. “California’s counties have long been a strong advocate for disabled access and the implementation of the American Disabilities Act,” said Scott McGolpin, director of public works for the county of Santa Barbara and president of the County Engineers Association of California, as reported by the California Asphalt Pavement Association, in CalAPA’s magazine California Asphalt.

“We recognize people with disabilities need and deserve safe access to freely move within their communities,” McGolpin said. “Counties have adopted cost-effective strategies to maximize our limited financial resources to preserve all of our transportation infrastructure.”

The new federal guidance, however, places additional hardships on cities and counties, he said. “Unfortunately, the new ADA Joint Technical Assistance forces local governments to modify existing infrastructure at significant additional costs, including reconstructing existing ADA accommodations that met previous federal standards. Consequently, it will minimize counties’ abilities to provide new access to other areas of the community.

“Despite this impractical update,” he adds, “counties will strive to reach substantial compliance without any additional resources to meet this unfunded federal mandate. Counties welcome the opportunity to work with federal partners to come up with a sensible solution.”