Why, when the equipment was getting better, were emergency repair rates creeping up decade after decade?

According to Preston Ingalls, president and CEO of TBR Strategies, in the 1950s an operator was expected to be a fair mechanic and take good care of his machine. A well-rounded operator back then knew how to use his eyes and ears and sense of smell and his ability to detect unusual vibration to tell when something was starting to deteriorate.

Today, says Ingalls, everybody is specialized. Operators operate and mechanics take care of the equipment. Trouble is, the typical mechanic or service tech may be responsible for dozens of machines and may only spend an hour or two with each one every few months. That’s no substitute for the kind of care a well trained operator can provide for a machine he works with 20 to 40 or more hours a week.

A properly-trained operator can detect 70 to 75 percent of all potential failures, Ingalls says. And companies that have trained their operators and instilled auditing and accountability procedures substantially reduce equipment downtime and the cost of repairs.

Five elements

In an operator care program, there are five basic things on which you should train your operators, says Ingalls.

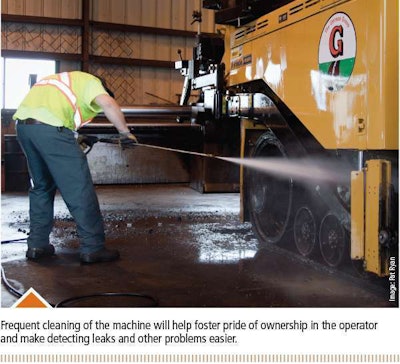

1. Knowing how to tighten, lubricate and clean components and when to do so.

2. Inspecting, detecting and correcting deficiencies before a machine runs to failure.

3. Maintaining correct operating procedures. “Teach them not just how to operate the equipment, but how the equipment operates,” Ingalls says. Accidents, neglect and abuse are substantial contributors to equipment failures.

4. Improving design issues. This isn’t solely the operators’ responsibility, but train your operators to communicate with mechanics and fleet managers. Encourage them to speak up about access problems, ergonomic issues, any design element of the machine they think isn’t right. Form EITs, or equipment improvement teams to collect these suggestions and take countermeasures where you can. You should also communicate these concerns to your dealers and OEMs.

5. How they can elevate their skills. Give them the basic mechanical knowledge and skills they need to do simple maintenance, troubleshoot issues and understand how the machine works and reacts. Another part of this is ensuring they repair it with a “fix it right – fix it once” mentality.

There are typically three periods of time operators can perform these chores:

• The beginning of the shift

• During down time such as waiting for the trucks to deliver asphalt

• At the end of the day. “If you look at a typical day, eight to 10 hours, you can find 20 to 30 minutes,” says Ingalls. “If you have time to lean, you have time to clean.”

Calling CLAIRE

The CLAIRE system breaks PMs down into two categories. Type 1 PMs are operator performed and done daily and weekly. A description of these can usually be found in the OEM manual that comes with the machine. Type 2 PMs, on the other hand, are done by skilled tradesmen, such as a mechanic or technician, on a schedule, typically timed to coincide with a PM, oil change or other regular maintenance.

It takes about four hours to training your operators and maintenance staff on the 5-step program and CLAIRE procedures. A lot of people train at the beginning of the season, before production swings into high gear, says Ingalls. If you’re not seasonal, you’ll have to pick a time, perhaps between big jobs. But you get more bang for your buck at the beginning of the season than after, he says.

A key element in an operator care program are your standards. The details of the daily and weekly tasks should be printed out on a laminated card and placed in a water proof black box or somewhere on the vehicle. These tell the operator what to do, where to do it, when to do it and how well.

Measure and monitor

In addition to training operators, you need a process to monitor and record what they’re doing. If you rely on paper or digital records kept by the operator, there is the temptation to pencil whip the results, checking off the boxes without actually performing the work.

To prevent this, Ingalls says you should train and field a group of “auditors,” people whose job it is to periodically inspect the machines and verify that they are well maintained and in good running order.

About a half day of training is needed to create an auditor, says Ingalls. These can be anybody in the company – executives, estimators, engineers, support staff, supervisors – not just technicians or shop personnel. Ingalls recommends against using operators or foremen for auditors. Operators tend to be less objective, and it’s problematic to take a foreman off a busy job, he says.

A typical construction company will need 10 or 12 percent of its employees to conduct audits. An average audit will only take about 30 minutes, says Ingalls, plus windshield time. And the average auditor should be able to handle three to five inspections a month.

Start with your critical equipment first, your mission essential machines, Ingalls says. What your auditors are looking for is visible evidence that shows that the operator is maintaining this equipment to standard. Is the cab clean? Are the fluids at the proper level? Have the filters been changed? Is the machine clean overall?

Proving justification

Selling company executives on an operator care program isn’t difficult once you show them how much they are spending on emergency maintenance and losing on downtime compared to others in the industry, says Ingalls. “Once they see that and the fact that they’re nowhere near world-class levels, it becomes a business opportunity.” The savings achieved in programs like these drop straight to the bottom line. They are pure profit.

Operators are likewise easy to convince, Ingalls says, because they know the frustration of equipment that’s not running well, breakdowns and delays. “We tell them they can make those headaches go away,” says Ingalls. Another way is to appeal to their sense of pride and ownership. “It’s just like getting a teenager to help wash and wax the car. At the end of that experience they have a greater sense of pride in that vehicle,” he says.

You should also have an incentive program and reward those who participate. The rewards don’t have to be big, since the public recognition of a job well done is most important.

Once you have a program up and running, you maintain it with lots of follow up and follow through – slow but persistent nudging, Ingalls says. “This isn’t something you’re going to create overnight. It takes a long time.