Liebherr models L550 through L586 have a new power standard power-split transmission. Using both a mechanical and a hydrostatic drive, the design captures the best of both. The hydrostatic is used for short loading cycles, while the mechanical is used for longer distances and uphill sections. A continuously variable transmission (CVT) automatically adjusts between the two drives, matching the drive type to the job at hand.

Liebherr models L550 through L586 have a new power standard power-split transmission. Using both a mechanical and a hydrostatic drive, the design captures the best of both. The hydrostatic is used for short loading cycles, while the mechanical is used for longer distances and uphill sections. A continuously variable transmission (CVT) automatically adjusts between the two drives, matching the drive type to the job at hand.Transmissions

Two types of transmissions are commonly found on wheel loaders: hydrostatic and torque converter. With torque converters, the lock-up feature is standard on some models and optional on others. “Hydrostatic is simpler and has fewer moving parts,” says Mike Stark, product specialist, heavy wheel loaders with Doosan. “Another benefit of hydrostatic is better power management and, with that, better fuel economy.

But, hydrostatic transmissions generate more heat than torque converter transmissions at higher speeds and in demanding applications. Hydrostatic is generally better in short run applications, while torque converters work better for longer runs. Both hydrostatic and torque converter are well-established technologies, familiar to both operators and service personnel.”

Modes match performance to applications. The fully automatic, electronically controlled ZF AS Tronic transmissions in Hyundai loaders have three modes, for example. Automatic Light (AL) is for traveling longer distances at higher speeds. Automatic Normal (AN) is for mixed applications that involve both short travel distances and occasional longer travel. Automatic Heavy (AH) is for use in constrained environments, such as all-day V- or L-pattern loading.

“With multiple modes, a self-adjusting clutch and self-diagnostic capabilities, these transmissions provide maximum productivity while controlling owning and operating costs,” says Corey Rogers, marketing manager, Hyundai Construction Equipment Americas.

Operators of Caterpillar loaders can choose from three modes that shape overall machine response. Hystat mode provides aggressive engine braking and enhances productivity in loading operations. Torque converter mode allows freewheeling on descents and around corners, reducing both operator fatigue and fuel use. Ice mode enhances traction in slippery underfoot conditions. “Our 926M, 930M, and 938M small wheel loaders all have this Powertrain Mode selection, since it’s part of the Caterpillar Intelligent Hydrostatic powertrain system,” says Joel Grimes, small wheel loader marketing engineer.

Common practice in short-cycle loading is to shift from forward to reverse, or vice versa, and rely on the torque converter to slow the machine in the midst of the direction change. RBB recognizes deceleration brought about by use of the forward/reverse lever and uses speed, direction and throttle position to apply the service brakes. The operator handles the machine the same way as before, but RBB provides smoother deceleration and direction changes. Torque converter wear is reduced, since it is no longer used for deceleration.

“OptiShift provides fuel savings during travel, on inclines and in load-and-carry operations,” says Eric Yeomans, product manager of wheel loaders, Volvo. “Reverse by Braking provides benefits during short-cycle loading. This means there are improvements to productivity and fuel efficiency regardless of how the loader is being used.”

In keeping with its business model of providing full performance but fewer frills at a lower initial investment, SDLG equips their loaders with ZF manual powershift transmissions that feature no modes at all. There is a manual kick-down, which most operators use to toggle between first and second gears throughout their work shifts. SDLG offers an aftermarket joystick that combines kick-down and F-N-R selection with standard joystick functions. “Probably 80 percent of our loaders go into simple loading operations,” says Nick Tullo, sales manager for SDLG. “This simplified approach to transmission management works well in those applications.”

Three speeds are enough, since electric motors have broad, flat torque curves. The transmission has no reverse; the electric motor is reversed to provide reverse travel. Energy is recovered on trailing throttle to slow travel speed and to power hydraulic circuits. When the operator lifts from the throttle, roll control can simulate either torque converter transmissions with freewheel, or hydrostatic drives with deceleration. Hydrostatic emulation reduces the need to use service brakes in V-pattern loading.

“In most loading applications, the 644K Hybrid takes advantage of the near-constant torque of the electric motor and the machine rarely leaves first gear,” says John Chesterman, product marketing manager of 4-wheel-drive loaders, John Deere. In typical loading applications, Chesterman says, a traditional loader is running at 100 percent of engine output, whereas the hybrid is running at 25 percent. The combination of a smaller engine and lower demand from the engine creates exceptional fuel efficiency.

Cab and controls

OEMs have been touting cab size growth in smaller machines, but bigger isn’t always better with these larger loaders. “In mid-size loaders, what matters more than sheer size is configuring space, providing connectivity for electronic devices and maximizing storage options,” says Chesterman.

Stark notes that smaller components open up more space without making cab dimensions any larger. “Doosan made the steering column smaller from the floor to the top. And because membrane switches take half the space of rocker switches, we were able to make our panels smaller.”

Komatsu America redesigned their cabs when moving from -6 (Tier 3) to -7 (Tier 4 Interim) models. There was a new console, standard rearview camera, and slightly more leg room achieved by moving the seat back a bit.

The current -8 (Tier 4 Final) models retain these features, and have further increased comfort with the inclusion of Sears Seating seats. HVAC saw no significant changes; it worked well already. “It’s a set-it-and-forget-it function,” says Craig McGinnis, product marketing manager of wheel loaders, Komatsu.

Most OEMs offer air-ride seats as either standard equipment or as an option. SDLG directs customers to the aftermarket for air bladders to convert their mechanical suspension seats to air ride.

Much of an operator’s comfort comes from the response characteristics of the loader. The eco-pedal feature on Hyundai loaders provides feedback by way of resistance (at the throttle pedal as the engine reaches 90 percent or more of its maximum rpm) to help operators stay in the more fuel-efficient range of engine speed.

With the Caterpillar Intelligent Hydrostatic system, operators control engine speed with the right pedal and travel speed with the left pedal. “This allows operators to enjoy quick cycle times with high RPMs, along with full control of both speed and wheel torque during the dig cycle and when approaching trucks and hoppers,” says Grimes.

OEMs work to control vibration and sound levels in the cab. Silicon oil-filled viscous cab mounts mute vibration, which helps reduce noise levels. Bruce Boebel, senior product manager of wheeled products, Komatsu, says Tier 4 Final provided an opportunity to design sound control into engine and aftertreatment systems. “The Komatsu Diesel Particulate Filter is actually a better silencer than most conventional mufflers.”

Volvo offers an option that continues to circulate engine coolant and run the cab fan on low during periods of shutdown. Unlike auxiliary power units used on line-haul trucks, this option won’t maintain a heated interior indefinitely or provide air conditioning, but it will keep the operator’s environment noticeably warmer during lunch breaks and other short periods when the engine is not running.

Visibility

Operators want 360 degrees of visibility, but there are key areas where visibility matters most. To load efficiently, they want to see the bucket. They want to see the front tires in order to detect slippage while charging the pile. And, to operate safely, they want to see behind the machine.

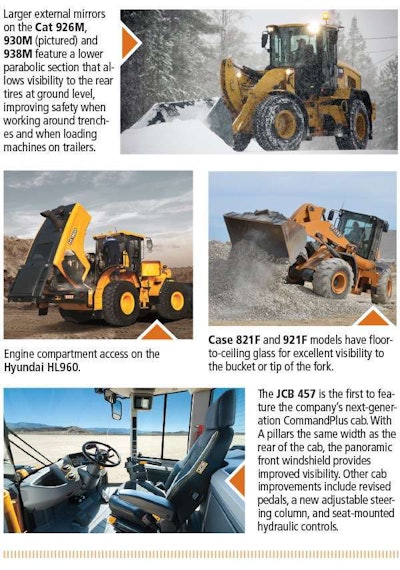

Most loaders now come with a 4-post ROPS cab. Where OEMs choose to position the A pillars can have a big effect on visibility. JCB moved the A pillars of their CommandPlus cabs out to the same width as the rear of the cab to provide a panoramic front windscreen and larger interior. All switches and auxiliary controls have been repositioned on the right hand A pillar, creating a simplified interior and providing easy access to controls.

Visibility behind the loader is a little more complex. Some OEMs have rear-view cameras as standard; others offer cameras as options.

Deere’s optional cameras have multiple modes, including always-on and on-in-reverse only. “But cameras are vulnerable to rain, dirt, and glare from direct sun,” Chesterman says. “They can be helpful, but should be considered a secondary visibility asset with unaided visibility the primary concern. One key is finding the sweet spot between cab size and operator placement for visibility.”

A big part of the rear-view equation is the size of the hood. Tier 4 Final engines (with exhaust aftertreatment and larger cooling systems to handle their higher rates of heat rejection) need more room under the hood. Accommodating this without obscuring the operator’s view to the back of the machine is tricky. An OEM’s ability to factor this in influences what additional apparatus, if any, will be required to provide rear visibility.

Several OEMs offer, or are developing, rear object detection systems, much like those found on passenger vehicles. No OEM is currently offering 360-degree cameras on loaders, although some aftermarket cameras are now available.

The addition of side mirrors greatly enhances safety when working near trenches and when loading the machine onto a trailer.