Alcohol Poisoning

By Tom Jackson

Ethanol is a great social lubricant. It puts the buzz in booze, but it has the opposite effect on engines – especially small ones. It’s corrosive and loves water – think bourbon and branch water, scotch on the rocks.

When it was first introduced as a fuel in the 1980s it was a disaster. “At that time there were tremendous problems with equipment and vehicles,” says John Foster, manager of product compliance at Stihl. “Material compatibility issues were very common. Some cars just stopped in their tracks after getting a tank of that fuel.”

Automotive re-engineering

Since the 1980s most vehicle manufacturers have come up with gaskets, seals and fuel injection equipment that could handle the stuff. And most people burn through a tank of gas in a matter of a week or two, so the ethanol doesn’t have much time to absorb water out of the atmosphere. Some automobile manufacturers have even designed engines and fuel systems that can run on 85 percent ethanol or E85. These are distinctly labeled as “Flex-fuel” vehicles.

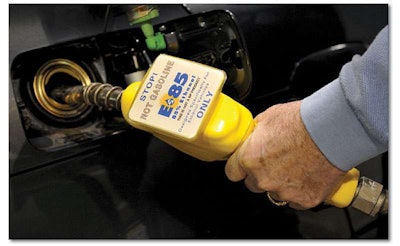

Today, unless you look hard, you won’t find any gasoline that isn’t blended with 10 percent ethanol, or E10 as it’s called. For most automotive and truck applications, this seems to be tolerable. (Although last year Lexus had to recall more than 200,000 cars to fix ethanol related damage.)

But if you use gas-powered equipment – jumping jacks, generators, concrete saws, jackhammers, powered screeds and trowels, breakers, post-hole diggers, welders and generators – ethanol still poses problems. Unlike automotive applications, where most users burn through a tank of gas in a week or two, the gas used in many small engines may sit for months at a time in unpressurized containers. Long storage times in open containers means the ethanol will absorb more water. Even pure gasoline will absorb some water and degrade over a season or so, but many small engine users report E10 gas going bad in less than two months.

Mechanic’s nightmare

Small engine repair shops across the country universally condemn the stuff and blame it for a rising tide of equipment failures and problems. To protect their customers’ equipment, several of the leading portable power equipment manufacturers are now selling their own proprietary ethanol-free gasoline. This gasoline is also premixed with lubricating oil for two stroke engines. It comes in sealed containers – you only use it as needed, so there is less opportunity for the ethanol to absorb water out of the atmosphere.

Pushback on E15

The EPA is now pushing for a new E15 ethanol mandate. The EPA’s justification is a law passed in 2005 called the Renewable Fuels Standard, or RFS, which requires the U.S. to use at least 36 billion gallons of renewable fuel annually by 2022. But the RFS law never took into account rising fuel economy standards, and Foster says he doubts the country can meet that goal even with E15.

The difference this time is that industry is pushing back against the overly aggressive promotion of ethanol.

In April, Kris Kiser, executive vice president of the Outdoor Power Equipment Institute told Congress: “No engine product in our legacy portfolio or coming off the production lines today is designed, built or warranted to run on any gasoline fuel containing more than 10 percent ethanol.”

Kiser also documented what might happen to small engines running on E15. This included excessive engine heat, melting of plastic guards, fuel leaks, evaporative emissions issues, unintended/early clutch engagement and permanent engine damage. (See Kiser’s full testimony at http://www.opei.org/news/detail.dot?id=17126). Ethanol has a higher octane number than gasoline so the likelihood of your engine racing on E15, rather than running at the correct speed, is considerable.

Additionally, nine automakers, foreign and domestic, told congress they won’t honor warranties on older vehicles running E15. In a public letter to Congress, Thomas Baloga, vice president of engineering for BMW in the United States wrote of E15: “Damage appears in the form of very rapid corrosion of fuel pump parts, rapid formation of sludge in the oil pan, plugged filters and other damage that is very costly to the vehicle.”

Leading the charge against E15 in Washington D.C., congressman Jim Sensenbrenner said, “Automaker responses overwhelmingly show that E15 will damage engines, void warranties and reduce fuel efficiencies. Americans need a fuel that will give them more miles out of a gallon of gas and extend the lives of their cars, not that will prematurely send their vehicles to the junkyard.”

Congress capitulates

This summer the Senate voted to end corn-based ethanol’s 45-cents per gallon tax credit given to the oil companies for blending ethanol with their gasoline. It looked like good news for anti-ethanol advocates, but the House refused to follow suit and let the bill die thus continuing a $6 billion subsidy for ethanol.

Even if a future Congress eliminates the subsidy, ethanol will have to be consumed in ever greater quantities unless the federal government repeals the RFS law. In fact, everything right now points to an E15 blitzkrieg that will sweep over the country within a year. The Government Accounting Office has said it may take up to a year before all the logistical problems are worked out in the ramp-up to E15. But the process is moving forward.

“In theory at this stage, E15 can only be used in flex fuel vehicles,” Foster says. “But you’re going to hear about some stations in the corn belt already dispensing E15 and there are questions as to the legality of that.”

Voodoo economics

One of the original justifications for E10 was that it would reduce imports of foreign oil and thus help our domestic economy. That hasn’t happened.

A research paper by Craig Cox and Andrew Hug for the Environmental Working Group showed that corn-based ethanol biofuel is wasteful, inefficient and a misuse of taxpayers money.

Other countries report similar results. In April the German news magazine Spiegel commented on that country’s brief flirtation with the fuel, writing: “An attempt to introduce the new biofuel mixture E10 in Germany has been a disaster. Even environmentalists oppose the new fuel.”

A step back for the environment

E10 blended gasoline was supposed to contribute less to ozone formation, a component of smog, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, according to the EPA’s studies. But that research has come under increasing criticism over the past few years.

Stanford University recently published a study that showed ethanol produces slightly more ozone than regular gasoline and produces emissions that are substantially higher than gasoline in aldehydes, the carcinogenic precursors to ozone.

And the list of American environmental groups opposed to ethanol in fuel is startling, including the American Lung Association, Friends of the Earth, the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Sierra Club, and the California Air Resources Board.

In addition to its unhealthy effect on our air, corn-based ethanol is widely criticized for consuming vast amounts of water, land and fertilizer. It takes 300 gallons of water to grow enough corn to make a gallon of ethanol. And diverting more than 40 percent of our corn crop to making fuel, critics say, is raising the cost of food across the globe.

What to do for now

Even if the EPA can convince gas station owners to put in additional underground storage tanks for E15, Foster says there is a great concern about misfueling. People filling their gas tanks may not check the pump label and inadvertently fill their gas cans, ATVs or portable power equipment from the same dispenser at the same time. If you’re a contractor and send a go-fer out to tank up the equipment next year you could be looking at a disaster if he chooses the wrong fuel.

Keep your eyes on those labels (especially if you live in the Midwest) and protect your portable power equipment with these suggestions:

1. Use manufacturer recommended fuel treatments for everything you put in your gas-powered equipment. Fuel stabilizers have been used for years and most manufacturers have additives now that help compensate for the effects of ethanol as well.

2. Get rid of any ethanol-blended gasoline after two months.

3. Find sources of ethanol-free gasoline. They’re rare, but most mid-sized towns will have at least one service station that sells it.

4. If your construction business is a major purchaser of portable power equipment, have a long talk with your dealers or manufacturers about the warranties on this equipment and get guarantees in writing. The long term effects of ethanol on small engines is not well known, but if your equipment isn’t lasting as long as it used to you may want to contract for extended warranties.