This is Part 2 of a four-part series on managing fuel costs as part of the Fuel Cost Volatility Survival Guide. (Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4 or download the entire guide.)

While the war in Ukraine is a convenient scapegoat for rising fuel costs, that conflict only exacerbated already escalating prices. Pre-COVID, energy producers had cut back on investment due to low fuel prices and other factors. They reduced output even further during the height of the pandemic, when the economy shut down, tanking consumer and business fuel consumption. When economies began fully reopening last fall, manufacturing resumed and people started driving, flying, and purchasing goods. Demand for fuel surged and producers could not keep up, further tightening oil markets and driving up prices.

Low fuel prices leading into the pandemic also curtailed the North American fracking industry, which relies on high oil prices to maintain profitability. And while rising oil prices make fracking viable once more, ramping up to resume fracking operations takes time, a problem further complicated by a shortage of sand used in the fracking process.

Against this backdrop, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February sent an already struggling energy market into a tailspin. With 11 percent of the world’s production, Russia is the third-largest oil producer in the world, behind the United States and Saudi Arabia, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Russia is also the world’s largest oil exporter. When world economies hit Russia with sanctions to protest its invasion of Ukraine, many countries including those in Europe that are dependent on Russian petroleum products were sent scrambling to find alternate suppliers, further roiling energy markets.

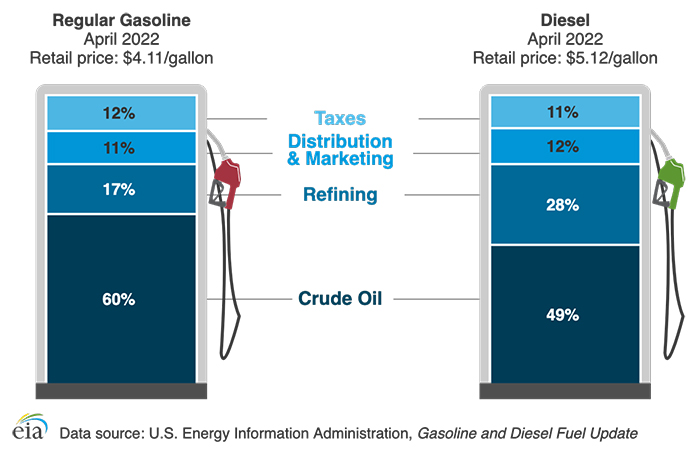

What we pay for in a gallon of:

All of this means there is less oil to go around – about 14 percent less than at the end of April 2021, according to the American Automobile Association. Back in March, to try and increase supply and lower prices, the International Energy Agency announced its 31 member countries would release 61.7 million in crude oil from their strategic reserves, more than half coming from the United States. The move had little effect on pricing because the planned release was small compared to the amount that flows daily from Russia. Similarly, with fuel supplies along the East Coast particularly tight, the Biden administration is considering a release of diesel fuel from federal heating oil reserves to address skyrocketing prices and the threat of supply outages.

In another effort to increase the global oil supply and drive down prices, the U.S. has begun lifting some sanctions on Venezuela. Meanwhile, after urging from the Biden Administration and others, OPEC producers agreed to increase monthly production, but supplies are likely to remain tight as the European Union works to implement a 90 percent ban on Russian oil imports by the end of this year.

With little hope these efforts will have much effect, experts predict the price of oil will not drop any time soon. A barrel of oil hit $120 on June 6, close to the 14-year high of $126 per barrel in March. And that has a huge impact on what we pay for fuel: crude oil makes up 60 percent of the price of a gallon of gasoline and nearly 50 percent of the price of diesel.

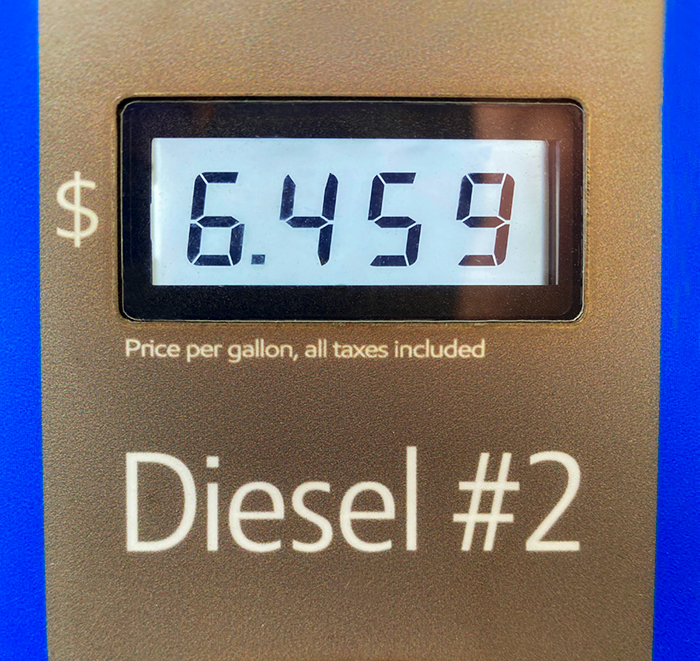

Why does diesel cost more than gas

Remember when diesel fuel prices were dependably lower than gas prices? Except during cold winters when demand for heating oil (made at the same time as diesel) pushed diesel prices higher? According to the U.S. Energy information Association, that has not been the case since September 2004 and here’s why:

- Demand for diesel and other distillate fuel oils is strong, especially in Europe, China, India, and the United States.

- The transition to lower-sulfur diesel fuels in the United States impacted diesel fuel production and distribution costs.

- The 24.4 cents per gallon federal excise tax for on-highway diesel fuel is 6.4 cents per gallon higher than the federal excise tax on gasoline.

Contractors and farmers who use red dye diesel fuel for off-highway equipment do enjoy the benefit of buying fuel sans the state and federal taxes. That saves on average 57 cents per gallon.

The second biggest factor in the price of a gallon of fuel is the cost to refine crude oil into the petroleum products we use daily. Unfortunately, during the pandemic, six refineries shut down, reducing our refining capacity by 4.5 percent. So as demand for fuel has increased, our ability to produce it has declined, further driving up prices.

Of the 129 refineries left in the United States, the newest with any significant production capacity is Marathon’s facility in Garyville, La., which came online in 1977. And the outlook for increasing refinery production is bleak. Despite refiners reaping record profits in the current market, building additional refining capacity is financially, environmentally, and politically daunting. In “The U.S. Can’t Make Enough Fuel and There’s No Fix in Sight,” Bloomberg sums up the problem: “The longer-term transition away from fossil fuels dims the outlook for demand, making companies unwilling to put up the billions of dollars needed to build new plants. Even resurrecting idled plants can be prohibitively costly at a time when construction and labor costs in the U.S. are booming.”

Facing limited success in affecting the two biggest factors in the price of fuel, Congress and some states are taking on the smallest cost driver: taxes. President Biden recently called for a 3-month federal fuel tax holiday - which would amount to about 18.4 cents per gallon for gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon for diesel - an idea that faces opposition even from fellow Democrats. Proposals to pause state fuel taxes, which fund interstate highway repair and mass transit projects, have also been introduced in more than 20 states, with only Georgia, Maryland, and Connecticut following through.

Politicians have been quick to point to corporate greed as the primary contributor to high fuel prices, but that is off base, a leading truck stop executive told Overdrive in May. The familiar refrain from Washington that oil companies are sitting on thousands of unused leases ignores the fact that they face serious labor shortages, long ramp-up times, and little incentive to invest heavily in wells that may soon dry up.

All of this points to one harsh reality: High fuel prices are likely here for the foreseeable future. Check out How to Manage Fuel Costs, to find out what you can do about it.