U.S. interchanges are undergoing a design shift; from the stale, split-phase, head-to-head configuration to high-volume, semi-continuous designs such as diverging diamond interchanges (DDI) and roundabouts.

Part of the impetus for this is the need to accommodate expanding numbers of motorists, as traffic volumes steadily increase. For the first six months of 2016, the vehicle miles traveled in the United States reached a record high of 1.58 trillion miles. That’s a staggering figure, and coupled with the fact that existing interchanges are more or less landlocked in their position, gives credence to the argument that intersection design needs a rethink.

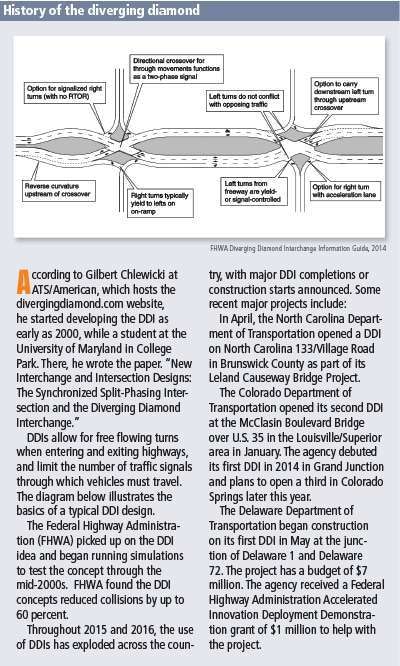

This is where interchanges, such as DDIs, fit in. Their designs eliminate conflicting left turns needed to clear opposing traffic, a feature that inherently improves safety and keeps traffic flowing.

Diverging diamonds

The Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) used Springfield-based construction firm Hartman & Company for the project, which ended up with several big wins: opening six months after construction started, coming in $7 million under budget ($3 million compared to a $10 million budget) and making use of the existing bridge.

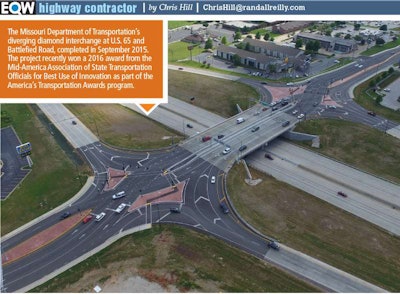

Fast-forward to present, and Hartman and MoDOT are still working together on DDIs in Springfield, which now has six of the intersections. Most recently, the two teamed up to complete a DDI at U.S. 65 and Battlefield Road, a project that won a 2016 award from the Mid-America Association of State Transportation Officials (MAASTO) for Best Use of Innovation, as part of the America’s Transportation Awards program.

“There were a couple of things that made us pick building something new at Battlefield and 65,” says Becky Baltz, district engineer for MoDOT’s Southwest District. “One is that the existing bridges were worn out, and the other was the heavy congestion through that interchange. We didn’t really have adequate turning lanes for all the traffic we had moving through.”

Baltz says that after looking at the design of the interchange and knowing the traffic patterns experienced there, that it was easy to determine that a DDI would move the traffic well, in particular because of the volume of traffic movements onto the ramps.

“The big driver of doing these things is not to be different; it’s really just an economical way to handle traffic volumes,” says Justin Wallace, vice president of operations for Hartman. “You look at one of these and see that for $3 million you can handle this volume of traffic with this design, or you could spend $10 million doing something traditional. To me, that’s the biggest advantage to them.”

While they are economical in the sense that DDIs take less time to construct, Wallace says, they do present more challenges than traditional interchanges. Much of that challenge comes from lane changes and switchovers that occur throughout the construction process. But, to combat that, MoDOT came up with another first for the country – a temporary DDI configuration during construction.

However, this configuration didn’t start off as smoothly as Hartman and MoDOT hoped. Wallace says the main challenge his firm faced while creating the temporary DDI was limited space, as they were trying to put it on half an existing bridge that was already too small. This space limitation caused flat angles coming into the interchange from the driver’s perspective, which also required a lot of signage.

“The first time we did that configuration was over a weekend, and we opened it up on a Sunday. That morning, it was a disaster with all the cars, and we expected that,” he says. “When we opened up with those flat angles, people thought it made sense to keep veering right, as opposed to veering left as is the design. It took a few hours to get it tweaked and dialed in to how it needed to be.”

Wallace says the more the lanes can intersect at 90 degrees, the better off they are, but in this case it was a necessity because of the way it had to be built.

“We only had a four-lane bridge, so each side had a through lane and a turn lane,” he explains. “To get this new bridge built, we had to shove all the traffic over to two lanes. So then, two lanes were carrying four lanes of traffic. Four lanes couldn’t even handle the flow before. It was wild how well the temporary DDI performed. There were a lot of skeptics about it, including myself, on how well it would work, but it improved traffic flow.”

“We really were kind of working on both sides, which is pretty atypical,” says Reid Catt, Olsson senior engineer.

He says a lot of the work for Hartman was the traffic control component – making adjustments to the phasing plan, and then the traffic control plan accordingly, and submitting these to MoDOT.

“It was interesting to say the least, because we were contracted with both the agency and the contractor,” Catt says. “Typically that doesn’t work out, but it did in this case with the experimental temporary DDI traffic control phase.”

In addition to keeping the traffic flowing, Catt says his firm was, in a way, also looking to create an innovative solution. “We knew we needed to maintain full access throughout construction, with exceptions for closures that had to happen, and meet the expectations of stakeholders near there,” he explains. “Somewhat superficially, we tried to think of something we could propose that would be different and set us apart. It snowballed from there in a brainstorming session. It looked like it would work and provide a benefit.”