Lee Archer Jr. has been a maintainer for the Connecticut Department of Transportation for 24 years and has seen many accidents and close calls while working along the side of the state’s roads.

He spoke of a supervisor being struck by a tractor trailer while picking up a piece of metal from the road and workers being killed while setting up orange cones. During a hearing before the state Senate’s Transportation Committee, he along with other members of a state employees union gave their support to a bill that would allow camera enforcement of speed limits in work zones.

“Every single day that we’re out there,” he said during the hearing February 27, “we’re putting our lives at risk.”

The bill is one of a handful of efforts around the country to allow automated speed enforcement in work zones, where the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reports that close to 800 people are killed each year in the United States.

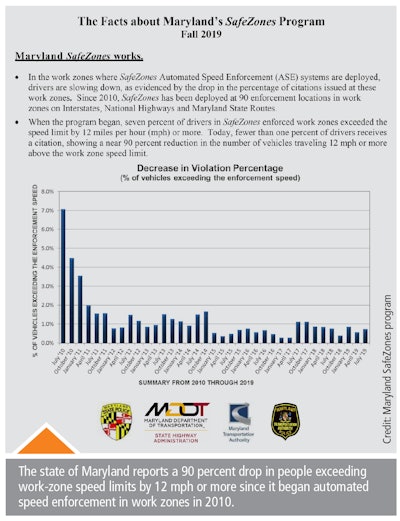

The bill is patterned after a law in Maryland, where the state has seen a 90 percent drop in the number of drivers traveling 12 mph or more over the speed limit since the camera enforcement took effect in 2010. This is according to data from the Maryland SafeZones Automated Speed Enforcement Program.

Pennsylvania is the latest state to put cameras in work zones, beginning enforcement the second week of March. Virginia’s state legislature passed a bill in early March approving the use of work-zone cameras in that state. (The legislation is awaiting the governor’s signature.) And other states like Connecticut, New York and New Jersey have bills seeking camera enforcement in work zones.

On the national level, organizations that represent road construction contractors are calling on Congress to allow states to use a portion of federal transportation funding to implement automated enforcement in work zones. The organizations, which signed onto a letter to Congress in December, include the American Road and Transportation Builders Association, the National Asphalt Pavement Association and the Associated General Contractors of America.

Brad Sant, ARTBA senior vice president of safety and education, says the association has heard from states that would be interested in implementing work zone speed cameras but don’t have the funding.

“Even 10 states picking it up and taking advantage of it could reduce the number of worker and motorist fatalities by a significant amount,” Sant says. “It’s going to hopefully come down from that 700 or 800 number (of deaths) we’ve seen for the past decade.”

For Archer and his fellow workers, that can’t come soon enough.

“The only way we’re going to be able to stop this is to slow people down,” he told the Connecticut Senate committee. “People have to be aware that we’re there.”

How it works

The rules and penalties for automated speed enforcement vary among the states that allow it.

In Maryland, the state most often cited by camera supporters, the SafeZones program is used only in work zones along expressways and controlled-access highways with speed limits of 45 mph or higher.

Violations result in a civil fine of $40, issued when a driver exceeds the speed limit by 12 mph or more. The cameras, which are fixed atop a white SUV and use light detection and radar (LIDAR) lasers to detect speeding, are operated through a contract with private company Conduent, which is paid a fixed fee per deployment. The tickets are reviewed by state police before they are mailed to the speeding vehicles’ owners.

At work zones with the cameras, drivers are warned ahead of time of the camera enforcement with signs, and there is also a digital speed display trailer that the program says is far enough ahead of the cameras to give drivers a chance to slow down. The state also posts the locations of the speed cameras on the SafeZones website.

In Illinois, the first state to enact automated speed enforcement in work zones, state police operate the cameras from within white vans that have digital speed displays on top. The minimum fine is $375 for a first offense and $1,000 for a second offense. If the second offense is within two years of the first offense, the speeder’s driver’s license is suspended for 90 days.

Pennsylvania begins enforcement

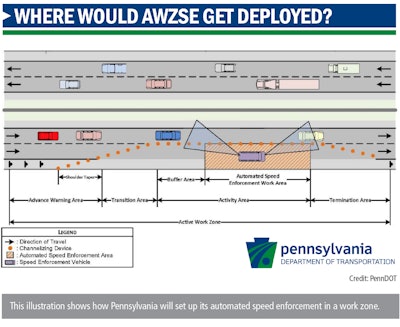

Pennsylvania completed a 60-day pre-enforcement period for its work zone cameras on March 4 and then began formal enforcement for a five-year pilot program.

“Overall, it generally appears that drivers are beginning to pay more attention to the posted speed limits,” said Jennifer Kuntch, just after the pre-enforcement period. Kuntch is the deputy communications director for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation.

The cameras will only be used when road workers are present in a zone on limited-access highways. Drivers going 11 mph or more over the speed limit will receive a warning on a first offense, a $75 fine for a second offense, and a $150 fine for subsequent offenses. Camera operation will be conducted by a private company and tickets issued by state police by mail.

“The program was implemented to reduce work zone speeds, change driver behavior and improve work zone safety for workers and motorists,” she said.

“The goal is to build awareness and, most importantly, to change unsafe driving behaviors,” adds Pennsylvania Turnpike CEO Mark Compton. “The program serves as a roadway reminder that safety is literally in each driver’s hands when they are behind the wheel.”

Not an easy sale

Though a few states have enacted automated speed enforcement in work zones, several others have rejected them.

Opponents cite privacy issues and concerns that the cameras are just revenue schemes for state and local governments and do little to improve safety.

A bill introduced this year to allow the cameras in Indiana passed a Senate committee but did not come to a full Senate vote due to opposition. Along with concerns about privacy, opponents were concerned about when a speeding driver is not the actual vehicle owner.

Some states have bills being considered that go so far as to ban cameras for any kind of traffic enforcement anywhere in their respective states. Under a Missouri bill, for instance, local governments using camera enforcement would have a year to complete or terminate their contracts with private companies. A similar bill is being considered in Tennessee.

The National Motorists Association opposes any camera enforcement of any kind. NMA Communications Director Shelia Dunn says there are better ways to enforce speeding in work zones than with cameras. On her travels, she says, she often sees work zones with confusing signs, or no signs at all, to alert drivers to the proper speed. She also believes digital signs that display drivers’ speed and police vehicles with flashing blue lights will cause drivers to reduce speed.

“I just think there are a whole lot of things you can do before speed cameras,” she says.

She also is concerned about abuse of speed camera revenues by government officials. “The local municipalities and even the state get used to having the money, and it really becomes a taxation-by-citation scheme,” she says. “It’s not about safety.”

Learning to compromise

Despite the opposition, supporters of speed cameras in work zones continue to press forward and have found that persistence sometimes pays off.

Though Indiana’s bill did not pass this year, Richard Hedgecock, president of Indiana Constructors Inc., was pleased that the bill made it out of committee.

“We look at it as a minor victory,” he said. “It’s the first time that legislation like this has gotten that far. It’s been introduced in the past, but it’s never even gotten a hearing.”

He vowed that his organization, made up of the state’s AGC and ARTBA chapters, would continue to push for the legislation until it passes. It’s especially important, he says, as the state is gearing up for major road construction.

“We’re about to see a huge increase in the amount of work being done on our highways, and with past experiences in work zones and acknowledging how the number of work zones is going to increase rapidly, we are looking for every way possible to make them safer places to work,” he says.

Charlie Goodhart, executive director of the Pennsylvania Asphalt Pavement Association, said it took nearly five years of lobbying by his and other organizations to pass the state’s automated speed enforcement law. Supporters agreed to a variety of compromises, such as tickets being issued at 11 mph over the speed limit and warnings for first offenses.

He also says the cameras are not about raising revenue. “This is nothing more than to save lives,” he says. “The bottom line is to save travelers’ lives and to save workers’ lives.”

“This technology works,” he adds. “It definitely slows traffic down or it gets people’s attention that you can’t be speeding through a work zone.”

What’s next?

Sant hopes that ARTBA’s and other associations’ push for federal funding will be successful and result in more states enacting laws to place speed cameras in work zones. He says the request has gained some Congressional interest and that it could be wrapped into a transportation reauthorization bill.

He’s also hopeful that just by focusing solely on cameras in work zones, the privacy concerns about cameras will be lessened. He says such laws should be specific about when and where the cameras will be used and to make sure the public is aware ahead of time that camera enforcement will be occurring. The cameras should also only be used when roadwork is underway.

“We know that if camera enforcement is going on and there’s not work going on, that just leads to motorists’ frustration,” he says. “There often can be a backlash.”

The program also can’t be a revenue generator.

“If the public views this type of enforcement as a revenue source instead of as a safety initiative, it will backlash,” he says. “It has to be done for safety reasons, not for revenue.”