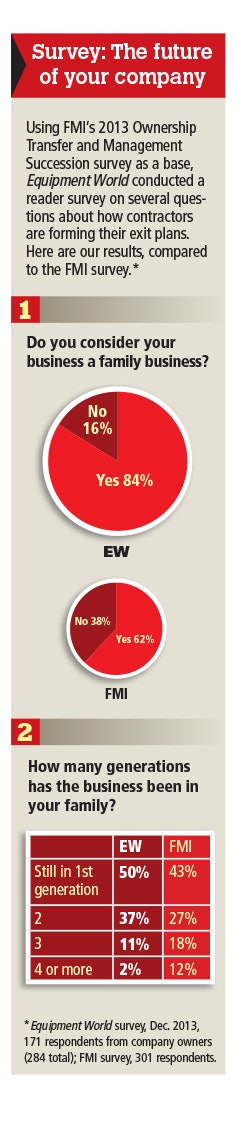

[Editor’s Note: This is Part One in a four-part series chronicling the stories of real contractors who are making hard choices about their end game in the business: liquidate? Sell to family or employees? Seek a third party buyer?]

Keith Andrews, president, RaCON Incorporated, looks at his nearly empty equipment yard from the driver’s seat of his pickup truck. “I always thought they’d scatter my ashes here,” the 55-year-old says with a wry laugh.

Andrews has sold off the majority of his 600-piece fleet, along with his office complex, which includes an 18,000-square-foot equipment shop. There will be little evidence of a once $125-million-a-year business, started by his mother Ramona Andrews in 1978.

Nearly 800 miles north, Triangle Excavators, a $3 million Holland, Michigan, earthmoving firm, began 2013 with a full roster of Michigan Department of Transportation jobs. But over the course of the construction season, partners Dianne Jacobs, 63, and Steve Krohn, 60, decided to stop bidding new jobs.

“We just needed to be done,” Jacobs says.

“The common sense is gone.”

While construction’s prolonged downturn serves as the canvas for both RaCON and Triangle, other factors came in to play in each owner’s decision to call it quits.

Dianne Jacobs and Steve Krohn

Dianne Jacobs and Steve KrohnJacobs puts the blame squarely on the frustrations of dealing with government work, to which the company transitioned after private work dried up in their area. “There are some great people that work for the Michigan Department of Transportation, but we just haven’t been running into them lately,” she says.

Jacobs says she’s seen older experienced inspectors take early retirement, only to be replaced by “junior inspector wannabes. They have very little understanding of what it takes to build a road. Their big concern is fulfilling the checklist of government requirements. I can work with anyone, but the common sense is gone.”

Krohn and Jacobs had talked about giving it one more year, trying to make it until 2015, but by this fall, they decided it was time to go. “You have to fight to get the work, you have to fight to get the work done and then you had to fight like cats and dogs to get paid,” she says. “It sounds like a crybaby story, but when you think, ‘I don’t want to go into work and fight that fight again today,’ you’re in the wrong place.”

“The calls from buyers stopped”

For Andrews, the decision was much more prolonged.

But Andrews wasn’t alarmed. RaCON had almost $220 million in backlog, and made a profit in both 2008 and 2009, with $54 million in equipment and 600 employees. It was the site developer for a steel mill in south Alabama, did highway work in three states, and worked on a number of commercial jobs.

“Our good fortune was almost a curse because we didn’t react as fast as we could have to the economy,” he says.

In November 2009, a bout of swine flu put Andrews in home quarantine for a week, and he immersed himself in business news. He came away with a clearer picture and new resolve. Gathering his managers in the office on a Saturday morning, he passed out racing-themed hard hat stickers that said “RaCON Inc. Endurance 500, Nov. ’09-Mar. ’11.”

“I told them we were going to have 500 days of tough times, but that we’d consider it an endurance race, not a sprint. I thought if we could get to March 2011, the economy will start to upturn and we’ll be OK. And if not, we’d have to make some serious decisions.”

It was a good plan, says Andrews now, and “my guys performed well, but we just couldn’t make a profit in that time frame, and I didn’t see the economy getting better.”

“Keeping us with the company was not an option”

Andrews initially tried downsizing, selling $12 million in equipment. He then looked for a buyer. Despite a few overtures, no deal was made. It’s the people that tear at you, Andrews says. “Equipment is just an asset.” Some of Andrews’ employees had worked with the company for 25 years.

Jacobs and Krohn also considered selling, but quickly realized it wouldn’t work. “What’s Triangle without Dianne and Steve?” Potential buyers wanted the two to stay with the business. “But that was not an option,” she says.

“It was so easy and fun when we started, and it’s so not now,” Jacobs says, citing frustrations ranging from an inspector who refused to grant a weather extension even though he shut the project down due to weather, to MDOT’s refusal at first to prioritize competing road projects.

“We started the business in 1998,” she says, “and we have guys who have been with us since 2000.”

Since Triangle will not finish all of their jobs until spring, “we wanted to give them enough time to find a new employer. And they can be picky, because they’re all good guys.”

“Like a ton of bricks lifted off me”

When the sale possibility became a dead end, Andrews decided to liquidate.

“Once I made that decision it was like a ton of bricks lifted off me. I could stop worrying about trying to find something for my people and equipment to do.”

A shot from the March 2013 RaCON equipment auction. The auction brought in $26 million.

A shot from the March 2013 RaCON equipment auction. The auction brought in $26 million.Andrews knew he would take a hit when his equipment went on the auction block. He hoped his fleet, with a fair market value of $38 million, would sell at $28 to $30 million; instead it brought in $26 million.

But the auction route had one thing going for it: 90 percent of his equipment would be sold in two days, rather than in a deal here and there that would extend the hassle.

On a cold March day last year, Andrews helped pass out hot chocolate to the bidders milling in his equipment yard. “People asked me if I was going to be able to go through it, and I said, ‘absolutely,’” he says. “It never hit me to feel bad about it because equipment is just an asset. It’s like trading in your car.”

And Andrews admits the fire to fight had left. “After 35 years, I was tired of the business. I had accomplished what I set out to do.”

When he was 17 years old, Andrews made a list of goals, ranging from owning 300 pieces of heavy equipment to making $10 million net profit in a year. “When I turned 50, I had accomplished all of them,” he says. “Maybe I felt like I had done everything I needed to do.” “It was a great run.”

So what now? “I have a couple of careers left in me,” Jacobs says. Under consideration: real estate, home building and design. Steve is looking at doing some estimating down the road. “Both of us right now just want to wrap this up and look back on 15 years and say it was a great run,” she says.

Both Triangle and RaCON are finishing out the remaining jobs they have on the books. In RaCON’s case, Andrews’ mother Ramona, 73, and father Benton, 78, are in charge of completing a six-mile extension of the Baldwin Beach Expressway in south Alabama. “It’s a tribute to their 60-plus years of building highways that they’ll probably finish it ahead of time,” Andrews says.

In 2004, Andrews started Ikaros, a bridge building company, which he’s retained. “I want to continue to bid bridge projects, simply because there are not as many people in that market.”

He’d also like to consult; he’s open about sharing his experiences. “We’ve always ridden the cycles,” Andrews reflects, “but when you have three consecutive losing years, it becomes too much.”

The Future of Your Company, a 4-part series

Page: 1 2 3 4 5