Materials used to build roads are some of the most recycled and reused materials worldwide. So, it’s no surprise that a process that reworks the asphalt and cement from an existing roadway is growing as a quick and low cost solution for improved pavements.

This process – full-depth reclamation (FDR) – pulverizes an existing pavement and base materials, mixing the resulting mass with water and cement, and then repaving it as a base that can be finished with a concrete or asphalt overlay. It’s a process that’s been around for about 30 years.

FDR was once a laborious task, involving multiple passes, but now a recycler or reclaimer can just make one pass and pulverize the roadbed down to about 18 inches, leaving a trail of what looks like dirt to a bystander.

“Most people describe it as a garden tiller,” says Mandy Alston, project manager for Atlanta Paving & Concrete Construction in Norcross, Georgia. “I chuckle about it because it’s the first description you can give somebody.”

Atlanta Paving has been performing FDR projects for more than a decade; a time during which they have seen a steady increase in demand for the process. This demand has allowed them to grow from one full-time FDR crew, to three, Alston says.

“A company came down from Canada and started trying to break into the Georgia market with FDR,” Alston says. Atlanta Paving founder Ernie Lopez viewed the process at work, and liked what he saw. “Ernie saw that it was something innovative and believed it was going to be the next big thing.”

From that mindset, Lopez pushed ahead with FDR, purchasing a Wirtgen recycler and bringing on a full time crew and a superintendent. “He always had this thought that you’ve got to be on the cusp of what’s really going to change things around here,” Alston says.

Seeing is believing

But what’s problematic about a new process, no matter how innovative it may be, is convincing stakeholders that it’s as good as it looks on paper.

Convincing nonbelievers that FDR can provide a stronger and longer lasting roadway – one that can be opened up to traffic quickly – is one of the top challenges Atlanta Paving faces, Alston explains.

“People who don’t see it in person don’t understand it,” she says. “Until you get a person out there to see what that mixer does, it’s hard for some people to conceptualize what you mean: that I’m going to tear the road up, but that I will hand it back to you at the end of the day and it’s drivable.”

“It’s all about somebody seeing it work the first time. If they can see what the road looks like before, and they see it after, they can realize the difference. Then, when you show them the cost figures, it becomes a sensible solution at that point.”

Because of that visual challenge, Alston says using videos has helped, but taking some skeptics out to a site is the easiest way to get them on board with FDR.

Those cost figures Alston referenced can be as low as half of the total cost of traditional methods of tearing out old pavement. That lower cost attracts municipalities looking to stretch their paving budget, and the base strengthening is a plus for areas with subgrade and moisture problems. The latter helped Atlanta Paving win a contract for a project on Senoia Road in Tyrone, Georgia.

“They ended up patching two or three areas 12 and 15 inches deep, and the city engineer said ‘What am I going to do? I didn’t know this road was going to fall apart,’” Alston says. “I told him we could fix it. We dropped in and did them a favor and mixed the road.”

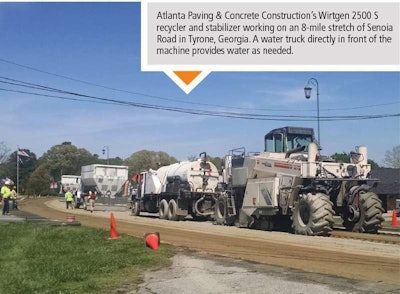

The city engineer was impressed, Alston said, and that favor is what led Tyrone to consider FDR for an 8-mile section of Senoia Road; a roadway that serves as the main street for the small town. While getting the contract was relatively easy, and the FDR work was straightforward, navigating the surroundings gave Atlanta Paving challenges.

The road traveled through a diverse landscape. A rock quarry, asphalt plant and several warehouses were on one end, along with a cement supply terminal. With multiple trucks going in and out of these businesses, dealing with traffic was a significant problem.

At the other end were high-end houses, and at near center, were the town hall, an elementary school, a historic cemetery and a soccer park. In addition, there were two railroad crossings.

“Everybody else looked at the job thinking it was scary and a lot to deal with,” Alston says. “But with some planning and some detours, we were able to work a lot of the traffic out and not bother people nearly as much as was expected.”

Equipment finesse

While Atlanta Paving uses a Wirtgen 2500 S for the pulverizing and mixing for the bulk of its FDR work, Alston says it takes multiple machines to provide quality results.

“We always use a sheepsfoot roller on our jobs,” she says. “The Georgia DOT doesn’t require and spec them, but for compactive efforts, especially when you’re doing 10 and 12 inches of material, putting that sheepsfoot roller on it is just a necessity.”

And to finish off the pavement, Alston says a milling machine is their secret weapon. “We keep a Roadtec 700 milling machine with every mixing crew, because you’re either milling off before or milling excess material off at the end,” she explains.

“Everyone wonders why our pavements are perfectly smooth. It’s because we take the effort to make sure it is. It’s amazing what the milling machine will do for trimming that last little quarter of an inch that needs to come out.”

Alston says using the milling machine doesn’t negate the work of motor grader operators, it just provides that final brush stroke of finish work.

“The key to FDR is getting it set quickly,” she says. “So, no matter how quick your grader operator is, you’re going to have to set that material. Chipping it out with a milling machine is the answer.”