According to AAA, pothole damage costs U.S. drivers roughly $3 billion a year, with roughly 16 million drivers experiencing some form of pothole damage to their vehicles over the past five years.

“On average, American drivers report paying $300 to repair pothole-related vehicle damage,” says said John Nielsen, AAA’s managing director of Automotive Engineering and Repair. “Those whose vehicles incurred this type of damage had it happen frequently, with an average of three times in the past five years.”

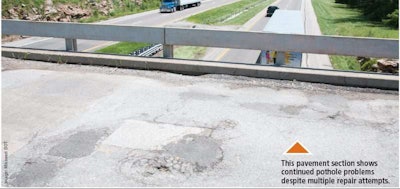

The public perception of pothole repair in a community can be limited to nothing much more than one worker filling a hole with a bag of cold patch, followed by a quick tamping or a simple drive-over with a truck. This perception is further clouded with the resulting crumbling and cracking a short while later on the same spot.

From city to county to the state level, transportation governing agencies put a lot of effort into repairing potholes. Many offer multiple means for the public to notify of pothole locations, from apps, to websites and hotlines. But identifying and locating them isn’t the issue. It’s the efficient and thorough repair that’s the concern.

In the quest for better solutions, contractors and transportation departments are turning to other options beyond the standard road crew fill and go.

Infrared heating

The asphalt heating is from within, as there are no exposed flames. This keeps the asphalt and oils from separating. The heated area is then sectioned off with the back of a rake, forming a rectangular working area, and then scratched up by the rake. A rejuvenator is then added to the asphalt and worked in, smoothed out and compacted using a tamper.

While this process isn’t necessarily new, it still hasn’t matured to a point where it is well known.

“Infrared repairs are virtually unheard of in many areas,” says Wesley Van Velsor, sales and marketing manager for New Hampshire-based Ray-Tech Infrared. “This makes contractors and their customers leery of the technology. If it is such a good repair method, they wonder why they’ve never heard of it before. The customers aren’t always willing to spend money on a repair that they may consider impossible, which makes it touchy for contractors to sell.”

“Compared to traditional cut and replace methods, infrared requires fewer employees per job, fewer labor hours and a lower fuel costs, whereas a cut-and-replace patch will eventually deteriorate from the edges inwards,” he says. “Infrared edges out cold patching techniques as it will outlast the cold patch materials and requires little to no additional effort.”

Right now, Ray-Tech is seeing roughly 75 percent of its equipment going to contractors, with the remaining 25 percent being bought by government entities.

The success of a pilot program at Prince George’s County Maryland could offer a boost of interest from the government level.

The county began a two-year pilot program for pothole repairs using infrared technology in 2015. Officials opted for the program due to its need to fill potholes in the winter with a system that would be more reliable than cold mix, according Darrell Mobley, the county’s director of public works and transportation.

Other contributing factors, such as hot mix asphalt not being readily available, and crews having to respond to weather events, also led to the pilot program.

“Our initial plan was to use this service in the winter, as it would be a more permanent repair,” Mobley says. “We expanded the concept and assigned the infrared truck to locations where there were numerous potholes in groups.”

Using the system provided by Pavement Corporation, the county has been able to repair between 17 and 21 potholes per day. “The time it takes to fill a pothole using the infrared process is comparable to the time needed to repair a pothole using the traditional pothole truck,” he explains. “The differences in the process are methodology and type of material used.”

Mobley says the repairs are in good to fair condition, but that some made during the winter and in inclement weather have experienced some degradation around the edges. However, he says the county and the public have been overall pleased with the results.

“The feedback from the public has been positive. With this methodology, squares are the end result of the repair. There have been a few complaints on the ‘checkered’ appearance of the road, but the infrared systems will be a methodology retained after the pilot program ends. However, how the system will be incorporated in our maintenance program for pothole repair has still not been determined.”

All-in-one

SuperiorRoads Solutions in Regina, Saskatchewan, produces an all-in-one machine, the Python 5000, which can be run by one operator who stays inside the equipment during the repair.

Scott Yasinski, SuperiorRoads vice president of sales, says the original idea behind the machine was to improve both safety and efficiency. With the design, the operator stays in the cab and doesn’t have to be on the roadway while work is being performed. “If we can keep people off the street, then we help reduce accidents in work zones and send people home to their families,” he says.

In his discussions with contractors and municipalities, Yasinski is finding that road crews repair potholes at rates ranging from about 40 per week to around 20 per day.

“This is reasonable when you consider three- or four-person road crews have to go out and set up their safety equipment and trucks and then get the work done,” he says. “With our machine we’re averaging between 22 to 25 potholes per hour.”

Yasinski also says this can translate to less than half the cost per ton to lay down asphalt with a traditional crew. The machine performs multiple tasks, including applying a blast of air to remove debris from the pothole, applying a tack coat, filling the hole with hot mix, then compaction.

The Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) used a similar one-man pothole machine during the 2015-16 winter season. With its fleet of five machines, RIDOT was able to patch more than 36,000 potholes in roughly a year’s time.

The agency directly attributes a dramatic drop in pothole claims to the ability of these machines. In an average year, RIDOT receives 560 pothole damage claims. For the 2015-16 season, they only received 151.

“Pothole repair just one of those places where so much money could be saved and much better jobs could be done,” says Yasinski. “There’s no reason to have so many potholes out there. And there’s no reason to have the public ticked off about what they see out there with road crews.”

The basics

No matter the innovation, proper pothole repair still boils down to the basics of preparing a surface correctly, according to Dave Anderson, director of sales for the government business unit for Bergkamp.

One of the biggest failures he sees in traditional pothole repair is not applying a tack coat.

“The tack coat does two different things,” he says. “One, it seals the area. So if you’ve got a lot of moisture that comes up, the tack coat seals it out. Two, it also provides an adhesion bed to get your mix on it. That’s going to be the same whether you’re doing a spray injection or you’re making the mix at the last minute and dropping it in.”

Contractors and government officials often cite time and money as the main reasons why they don’t apply a tack coat, Anderson says. “They look at this ‘extra’ cost and say, ‘Oh, that’s going to cost me.’ As a good example, at $5 a gallon for tack, they’re going to go through $20 a day. If they don’t use it, they’re going to go back for more repairs faster. It’s a pay me now or pay me later scenario.”

He adds that crews using systems like the Bergkamp SP Series spray injection pothole patchers follow four steps: cleaning, applying tack, filling and compacting. “When you go through that process, and you do it correctly and with the right materials, you’ve got a semi-permanent to permanent patch,” Anderson says. “Some people think they can take some of those steps out or take a shortcut, all under the idea that they’ve been doing it for 20 years. I don’t care if it’s 20 years or 20 minutes – if you skip some steps you’ve got the potential for problems.”

3D printing asphalt robots?

For a look at how potholes might be filled in the future, take a look at New Windsor, New York-based Addibots, which is proposing a robotic mobile 3D printer for this task. But instead of having material attached to the Addibot to print, the machine can use materials on a surface for construction.

The company has developed four generations of prototypes, with the last used as essentially a 3D ice printer on an ice rink, says Robert Flitsch, chief executive manager.

“These prototypes achieve proof of concept for many of the important systems behind our technology, such as surface repair applications like repairing pot holes and cracks in roads,” says Flitsch. “We’re now working on development of a fifth prototype that works with materials that will be used for repairing roads, such as asphalt or concrete.”

He believes his machines would be a step up in road repair work quality, as they would not require human intervention in the process. “With precision computer vision capabilities and high-resolution additive manufacturing methods, our robots can serve as far superior eyes and hands, vastly improving the skill of the workers using them in conducting repairs,” Flitsch adds. “Besides improving the skill of our workers, they will also improve workplace safety for our workers.”

Providing all goes well, Flitsch predicts he’ll have a product to market in three years.

![US 30 Topaz Bridge Completed 10_10_12 037[1]](https://img.equipmentworld.com/files/base/randallreilly/all/image/2016/07/eqw.US-30-Topaz-Bridge-Completed-10_10_12-0371.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)