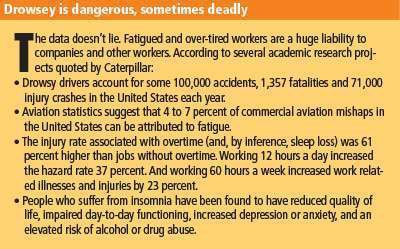

When it comes to accidents in the construction, trucking and mining space, however, Caterpillar Safety Services is now using a technology that can predict with significant accuracy the odds of someone having an accident, and when.

The heart of the system is the Cat Smartband, a simple and unobtrusive Fitbit-like device that feeds data into a software program that can tell when a worker is suffering from a lack of sleep and the fatigue that results. Some Cat customers are also using the Smartband with a complimentary driver safety system (DSS), which combines dash cams trained on the drivers and sensors on the trucks that monitor hard braking, swerves and other anomalies. Caterpillar has been using these systems at several mining sites for about two years.

The obvious benefit of using the Smartband and DSS systems is that they reduce the risk of sleep and fatigue related accidents. But, a deeper and more valuable benefit may be their ability to change habits and improve the performance and health of workers over the long term.

Todd Dawson, fatigue solutions manager at Caterpillar, heads up the Smartband program. He’s been studying fatigue science for 30 years after noticing as a young man that family members who worked night shifts always seemed to be grumpy, and those who worked in the day were happier. Since then, Dawson has been at the forefront of a scientific discipline called actigraphy, which studies the impact of poor sleep habits and fatigue on accident rates, productivity and a company’s bottom line.

Scientifically rigorous

Photo: The Telegraph.

Photo: The Telegraph.For the Caterpillar program, Dawson chose the wristwatch-type device from a company called Fatigue Science, one of the leaders in fatigue and sleep research. The device is sufficiently robust to stand up to the rigors of construction and mining work, and has best-in-class accuracy and specificity.

The Smartband measures motion with an internal 3D accelerometer. When you stop moving, it assumes you are asleep. That information is downloaded into a software program that looks at patterns of activity, and matches those with things like the time of day or how long it’s been since the person wearing the device last slept.

“From those sleep and wake patterns, you can then get a prediction of their effectiveness or alertness level,” says Dawson. “Are they effective and alert, or are they struggling? Are they at risk for having a fatigue-related microsleep incident?”

Temporary study

In the current applications, the SmartBand is worn 24/7 for about 30 days and then taken off. The data is used to study a person’s sleep habits, fatigue and awareness levels, and then as a basis to coach them to be more conscious about these.

During the study period, the wearer can push a button on the device and get a score, from zero to 100, relating to their current alertness level. “If they see they’re at 85, they know they’re doing good; but if they get a score of 60, they may realize they’re struggling,” says Dawson. “What’s interesting is when we come back to the jobsite, we find groups of people discussing their scores.” Instead of bragging about how little sleep they need to function, with their Smartband scores, drivers are more likely to brag about their alertness levels.

Coaching and health

At the end of the study period, Dawson goes back to the site and discusses the individual results with all the drivers who agreed to participate in the program. The results remain anonymous, but individuals know their scores. If the data suggests that somebody has trouble sleeping, this might indicate a problem such as sleep apnea, says Dawson.

Such data provides an extremely valuable snapshot of how well your crews are functioning, both short and long term.

“People who get less sleep or are more fatigued tend to have more sick days, so they are absent more,” Dawson says. “Their health care costs are higher and they are at higher risk of having an accident. I have seen studies that say heart disease is double the risk for people who are in that higher fatigue zone.”

Examining shift work

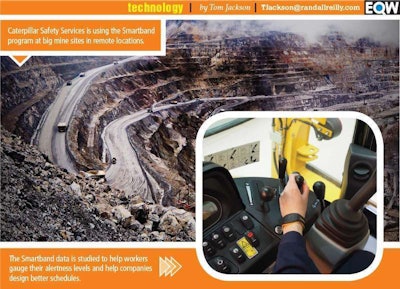

Mining companies are also using Smartband data to get a better idea of how to structure shift work in difficult to reach locations, such as the oil sands regions of Canada, Dawson says. Workers in a lot of these remote sites stay in a camp. Often, they fly in or take a long bus ride and work one or two weeks solid, and then take an equal amount of time off.

“What’s interesting is when I have people wearing the band for 28 days, even if I don’t know what shift pattern they are on, I can almost always tell when they’re in camp and when they’re home,” Dawson says. “When they’re in camp, they go to bed on time, they get good sleep, and they wake up on an almost military schedule. But when they get home, they’re all over the place. Their sleep is disrupted by kids, dogs, neighbors; they’re out partying. There are all kinds of distractions. But in camp, they do pretty good.”

Having the data is the first step towards making improvements. “You may inherently know a schedule is bad, but without some information or data, it becomes a very emotional topic,” Dawson says. “But if you have data to show that a specific schedule results in lower alertness scores, then you have a rational basis for discussing changes.”

In the program, only the individual volunteers see their own specific data. But the group data, collected anonymously, can be studied to find trends. “You can look at how one site performs vs. another site, one shift vs. another shift, or how people handle recovery after a string of night shifts,” Dawson says.

Driver monitoring

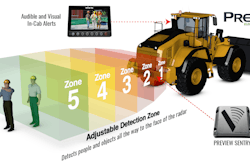

The DSS program also includes sensors that monitor the truck for events such as swerving, hard braking, excessive speed or driving away with the dump body raised. Software systems behind the camera and sensor inputs can determine if these behaviors constitute a high-risk driver and send out alerts telematically to dispatchers.

“We’re starting to see some interesting correlations where the watch is predicting a high risk zone for a driver and fatigue-related microsleep event in the cab,” says Dawson.

Expanded use

While Caterpillar’s Smartband solution is currently used in just mining applications, Dawson says there is no doubt that this and similar systems will migrate into the construction environment soon. Similar systems are already being used by the railroads, airlines, and oil and gas industries, he says.

“The haul trucks are an easy target,” says Dawson. “When you look at a dozer, or grader, or shovel operator, it’s a different type of work. We are doing some tests on those. But, because the field of view is different and people are looking in different ways, moving around a lot more, there are some challenges to make that a reliable solution.”