In 1998, Mike Brock was just three years out of high school when he began his construction career. He bought a small piece of land from a family friend for what he calls “a real bargain.” Then, following his grandfather’s advice, Mike began to sell sand off of the property. He soon sold his car, bought an old front-end loader and his career was underway.

After selling dirt and sand, Mike started doing grading and land clearing jobs, which eventually lead to work at the local Duke Energy nuclear plant and other major clients in the Hartsville area. Mike took his grandfather’s advice again and bought a 1960 dump truck, a truck that he still owns to this day.

The company’s commitment to clients has been noticed and it’s why companies like Duke Energy Progress go back to him time and time again. Says Carson Lee with Duke: “If you’ve ever worked in a nuclear plant, you know it’s a whole different animal. He totally understands what’s required for this work environment.”

“He’s great at empowering his people and letting them do what they’re good at,” adds Jeff Jones with Blanchard Machinery. “Whereas some contractors can be very controlling, he’s smart enough to know he’s got to give a little every now and then and let someone have some ownership over a situation. I think a lot of people could learn from his leadership approach.”

Sound financials

Brock has seen his business go from just himself and his grandfather digging dirt to a $5 million company. He says he owes much of his success to the commitment of the people in his company in being fair with its customers. “You have to treat people well,” he says. “You have to make sure you have that loyal customer. If you don’t have that loyalty, you’re going to bottom out. You’re not going to survive.”

He also believes private life bleeds over into business life from a financial standpoint. His advice: don’t carry significant personal and business debt simultaneously.

“If you’re going to owe on your business, then you’ve got to have your other stuff paid for,” he states. “You can’t have a house with a $4,000 or $5,000 a month payment on it. It just doesn’t work out. You got to keep your debt to a certain level.”

He also feels contractors shouldn’t continue with a project if they aren’t being paid properly. While that should seem obvious, he says, some contractors will continue working, either due to a personal relationship or for fear of taking a hit to their reputation. And from experience, Brock has determined there is certain work he will not take on.

“I don’t do subdivisions, because they’re owned by investors,” he explains. “Investors hide behind LLCs and corporations. If they get in trouble, then you’re going to be stuck holding the bag.

“You’re in deep, always, in this business,” Brock continues. “So if you’re not working on a bonded job and you’re not first or second tier from a contracting standpoint, then you better be careful. Because if you’re not, you’re playing with fire and you will get burned.”

Brock says these are lessons he learned the hard way, and it it makes absolute business sense to be circumspect in his everyday business dealings, including being prepared for client shortcomings and obstacles.

“That’s one of the problems in the industry,” he says. “People need to understand the business side.” Brock recommends contractors stay on top of current legal and financial issues, to the extent he thinks management-level individuals should take refresher courses.

“Laws may have changed, so be careful because it could put you out of business,” he says. “But we’ve survived long enough now that we’re in good shape. We’ve learned enough about how bad things could get or how easily things could happen, to where we’ll probably survive.”

Brock says insurance is another key side of the construction business, explaining it could put a contractor out of business quickly. As with regulatory and financial issues, he says insurance coverage should be monitored closely.

“There’s nobody going to call me and tell me that I don’t have insurance on an excavator, for example. I’m not going to know I don’t have insurance on it until I try to collect if it burns. You got to really be careful with something like that. That $200,000 in that equipment is like having $200,000 in a 401k.”

To stay on top of these issues, Brock meets with his office staff once a month to review insurance needs. “We’ll pull this stuff out and I’ll say, ‘Have we caught this change? Is it covered?’ You’ve got to do it. It’s not micro-management, but everybody makes mistakes. You need to be involved with your business to a certain extent to protect yourself, because the unknown is what will get you every time.”

Taking care of equipment

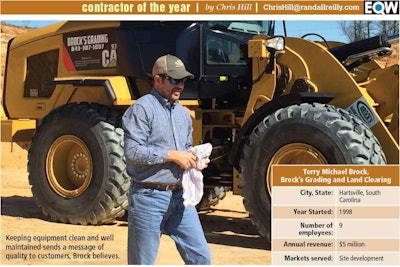

Brock believes in the adage that to be successful, you must look successful, and carries this over to the appearance of his equipment.

“I’ve got equipment with 8,000 hours on it that looks way better than people’s 2,000-hour equipment,” he says. “We never let the inside of our equipment look bad. That’s the price you pay for working for me. We handwash and wax the equipment. We’re not going to rub the paint off, we’re not going to dent our equipment. Every once in a while you’ll slam against something, but my operators are professional and take great pride in taking care of our equipment.”

This pride and the effort in maintaining his equipment is one of the key factors Brock says separates him from other contractors. “You got to have some pride in what you do. And if you take pride, a customer looks at your equipment and they say, ‘Well, if he takes that much pride in his equipment, he’s going to take pride in what he does, too.’”

And keeping equipment maintained properly adds to the bottom line, Brock says.

“You want equipment to last as long as it can. The first 4,000 hours you put on a machine, you’re not making a big profit. You make your profit on the end of its life. That’s when it’s paid for and that’s when you should make your biggest profits.”

Safety culture and experience

By the nature of his work at the Duke Energy nuclear plant, Brock has become adamant about safety, saying it is the most important thing in the construction industry.

“This will break you faster than anything else,” he says. “Duke Energy uses us because of our safety culture, because we’ll take advice, we’re slow and easy, and we keep nice stuff to work with.”

Without a good safety culture, Brock says a contractor is in trouble. The meticulousness of it is aggravating to an extent, he says, but it gives employees a taste of what needs to be done. To make it stick, contractors should expect employees to continue a safety culture on every job.

While Brock’s sense of safety issues are heightened because of his work at a nuclear facility, he believes such diligence can and should be carried across all construction work.

“Understand that the pre-job briefs that you have in the morning are so important, because they’ll keep you from getting hurt,” he says. “Slips, trips and falls are the leading accidents in construction. That’s where your OSHA recordables are coming from. It doesn’t have to be a fatality. You can trip over a rock on your jobsite and you can cost the company thousands of dollars. And you can keep yourself from getting good jobs, because they are based on your safety record, every one of them.”

Brock also believes a cornerstone to success in construction, from a business perspective and an individual perspective, is experience. “There are all kinds of opportunity in the construction industry,” he says, “but you can’t come into it right out of college and make that big money.”

A good path, Brock says, is for an individual to work for a reputable company and be willing to put in the time to learn through experience and “make an honest living to be able to demand that big salary.”

“Kids coming out of college with an engineering degree – they don’t have anything,” he jokes. “That degree is no good until you get here in the real world. They need to come out here and run a bulldozer for three or four years after they get the engineering degree. Then they’ll know what construction’s all about.”

“It’s not anything you learn in a book,” Brock adds. “You can get the basics from a book, but you’ve got to learn through situations in the field and all the different things that happen.”